If the astronauts suddenly drifted into the interstellar void, they would have to push their bodies to safety, kicking and waving their limbs toward a haven in the void.

Unfortunately for them, physics is not forgiving, leaving them floating without hope forever. If only the universe was curved enough, their defeat might not be useless.

Centuries before we left to pull the Earth, Isaac Newton succinctly explained why things move. Whether it is expelling the gas, pushing it on solid ground, or swishing the fin against the liquid, the momentum of the action is maintained by the sum of the elements involved, creating a reaction that propels the body forward.

Remove the air around the bird’s wing or the water around the fish’s tail, and the effort of each flap will push in one direction as with the other, leaving the poor animal fluttering weakly without any net movement toward its destination.

In the early twenty-first century, Consider the physicists loophole for this rule. If the three-dimensional space in which this motion occurs is curvilinear, changes in the object’s shape or position will not necessarily follow the usual rules of how momentum is exchanged, which means that it will not need a motive.

The curved geometry of spacetime itself could mean a distortion of an object – right kick, flutter, or flutter – you might just see a net subtle change in its position after all.

On the other hand, the idea that the curvature of spacetime affects motion is as straightforward as watching a rock fall to the ground. Einstein covered this over a century ago in his book General theory of relativity.

But showing how the rolling hills and valleys of deformed space may affect the body’s ability to self-propel is a whole other ball game.

To note this in action without traveling to the nearest space warp Black holeA team of researchers from Georgia Institute of Technology, Cornell University, the University of Michigan and the University of Notre Dame built a curved space model in the lab.

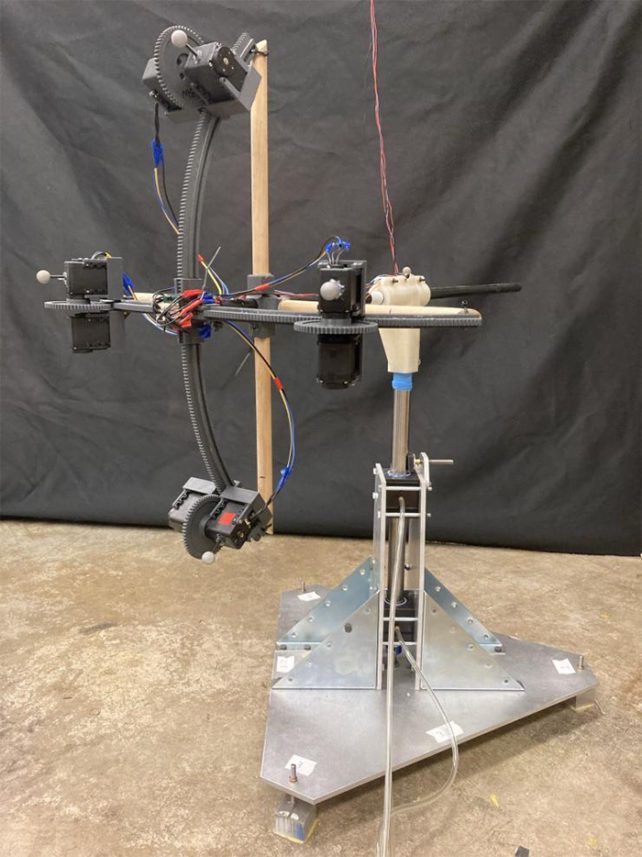

Their mechanical version of spherical space consists of a set of motor-propelled blocks driven along an arched crossroads of tracks. Attached to a rotating arm, the entire setup is positioned in such a way that gravitational pull and frictional drag are minimal.

- A “space” swimmer moving on the trajectory of a rotating arm arm. (Georgia Tech)

While the masses did not break with the physics that dominate our somewhat flat universe, the system was balanced so bends in the paths would have the same kind of effect as dramatically curved space. Or so the team expected.

As the robot moved, the combination of gravity, friction and bending were combined into motion with unique properties that could be best explained by the geometry of space.

“We let our shape-shifting object move in the simplest curved space, the sphere, to systematically study motion in the curved space,” Says Georgia Tech physicist Zip Rocklin.

“We learned that the expected effect, which was so counterintuitive that it was rejected by some physicists, did occur: when the robot changed shape, it moved forward around the sphere in a way that cannot be attributed to environmental interactions.”

boundary frame = “0″ allow=” accelerometer; auto start; clipboard writing. gyroscope encoded media; Picture-in-picture “allowfullscreen>

Although the effect is small, using these experimental results in line with the theory could help better position technology in areas where the curvature of the universe becomes significant. Even in cases of gentle regression as well as Earth’s gravity, understanding how contained motions can alter ultra-fine locations in the long term could become increasingly important.

Of course, the physicists were going the zero-fuel route.”Impossible Engines‘ Before. Small hypothetical powers in experiments have a way of coming and going, generating no end to the debate about the validity of the theories behind them.

More studies using more precise machines could reveal more insights into the complex effects of swimming over the sharp edges of the universe.

For now, we can only hope that the gentle gradient of the void surrounding the poor astronaut will be enough to see him reach a safe haven before the oxygen runs out.

This research was published in PNAS.

“Beer aficionado. Gamer. Alcohol fanatic. Evil food trailblazer. Avid bacon maven.”