Between 1993 and 2010, humans extracted and transported so much groundwater for our planet that it contributed to the migration of Earth’s poles.

The mere contribution of groundwater redistribution caused a polar shift of 80 centimeters (31.5 inches) to the east, according to a new analysis led by geophysicist Ki-Weon Seo of Seoul National University in South Korea.

These results allowed the scientists to confirm that previous estimates of groundwater depletion due to human activity equated to a total sea level rise of 6 millimeters over that period.

The researchers conducted this work to better understand the phenomenon of polar motion and the contribution made by changes in the distribution of water on Earth. In 2016, scientists made a breakthrough in discovering the cause of the Earth’s rotational poles wandering: the distribution of terrestrial water storage.

Seo and his colleagues have now determined how much groundwater moving humans contribute to this wandering.

“The Earth’s rotation pole actually shifts a lot,” Seo says. “Our study shows that among climate-related causes, groundwater redistribution actually has the greatest impact on shaft drift.”

It makes sense when you think about it. The Earth rotates on its rotational axis much like a spinning top. When the distribution mass around this axis changes and becomes uneven, the axis shifts to compensate.

Climate change has a huge impact on this. When frozen parts of the world, such as glaciers and ice sheets, melt, the distribution of water on Earth’s surface changes, and the poles — the ends of the axis of rotation — move.

This effect became prominent in the early 1990s, and much work has been done to determine the role that water redistribution plays in it. But the effect of groundwater extraction alone has not been isolated.

Based on climate models, Scientists estimate in 2010 Humans have pumped about 2,150 Gt of groundwater between 1993 and 2010, about 6 mm of sea level rise, but it has been difficult to confirm through observation.

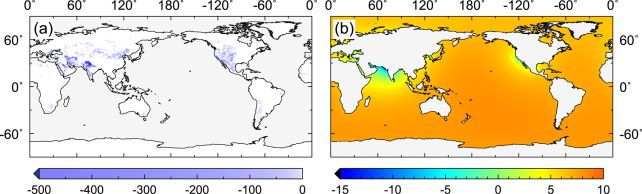

Seo and colleagues tackled the problem using polar motion observational data and modeling. First, they modeled polar motion taking into account the contribution of melting ice from glaciers, ice sheets and sea ice. Then, they added different levels of groundwater extraction to their models.

border frame=”0″allow=”accelerometer; auto start; Clipboard write. gyroscope encoded media; picture in picture; web sharing “allowfullscreen>”.

This took them closer to the observed motion, but the model only became identical when they used the 2150 Gt estimate.

The estimate provided the exact contribution of groundwater extraction. With the groundwater contribution not included, the model was offset by 78.48 cm.

Between 1993 and 2010, groundwater extraction pushed the Earth’s poles at a rate of 4.36 cm per year. (It may still be exerting influence, but the team’s work is based solely on data through 2010.)

“I am very happy to find the unexplained cause of shaft drift,” Seo says. “On the other hand, as a land-dweller and parent, I am concerned and surprised to see that groundwater pumping is another source of sea level rise.”

However, the findings could help mitigate further polar motion. The greatest effect is seen when groundwater is extracted from mid-latitudes. The researchers found that most groundwater extraction between 1993 and 2010 occurred in mid-latitudes, primarily from North America and northern India.

If these regions make a concerted effort to reduce rates of groundwater extraction, it could help slow polar motion and sea level rise. However, the researchers say that such an effort should continue over a long period, at least decades.

But working to mitigate human impacts on the climate is a long game. The earlier you start, the better.

“Observing changes in the Earth’s rotational pole is useful for understanding differences in water storage at the continental level,” Seo says.

“Polar motion data has been available since the late 19th century. So, we can use this data to understand the differences in continental water storage over the past 100 years. Were there any changes in the hydrological regime caused by a warming climate? Polar motion can hold the answer.” .

Research published in Geophysical Research Letters.

“Beer aficionado. Gamer. Alcohol fanatic. Evil food trailblazer. Avid bacon maven.”