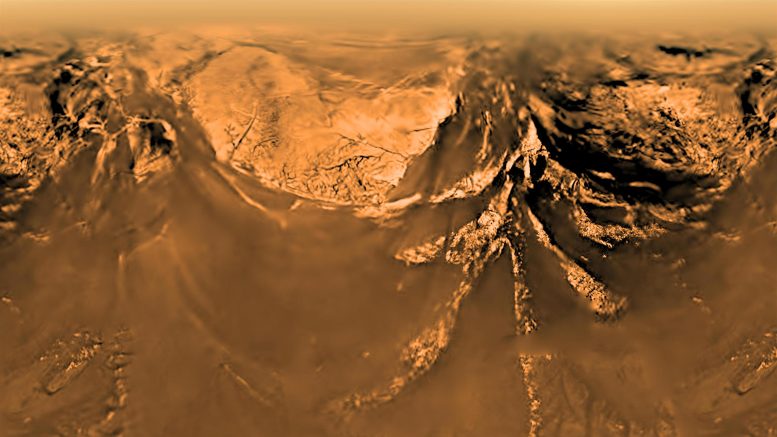

This poster shows a flat (Mercator) projection of the Huygens probe's view of Saturn's moon Titan from an altitude of 10 km. The images that make up this scene were taken on January 14, 2005, using the lander imager/spectroradiometer on board ESA's Huygens probe. The Huygens probe was delivered to Titan by the Cassini spacecraft, operated by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. Image source: ESA/NASA/JPL/University of Arizona

An astrobiologist has discovered that Titan may not contain enough amino acids for life to arise.

A study by Western astrobiologist Katherine Nish showed that there is an ocean under the surface of Titan – the largest moon Saturn – It is most likely an uninhabitable environment, meaning that any hope of finding life on the icy world is dead in the water.

This discovery means that space scientists and astronauts are unlikely to find life in the outer solar system, home to the four “giant” planets: JupiterSaturn, Uranus And Neptune.

“Unfortunately, we will now need to be less optimistic when searching for extraterrestrial life forms within our solar system,” said Nish, a professor of earth sciences. “The scientific community has been very excited about finding life on the icy worlds of the outer solar system, and this result suggests that it may be less likely than we previously assumed.”

Impact on the search for extraterrestrial life

Identifying life in the outer solar system is an important area of interest for planetary scientists, astronomers, and government space agencies such as… NASAThis is largely due to the belief that many of the giant planets' icy moons contain large subsurface oceans of liquid water. Titan, for example, is thought to have an ocean beneath its icy surface that is more than 12 times the size of Earth's oceans.

Katherine Nish, Professor of Earth Sciences. Credit: Western Communications

“Life as we know it here on Earth needs water as a solvent, so planets and moons that contain a lot of water are important when searching for extraterrestrial life,” said Nish, a member of the Western Institute for Earth and Space Exploration.

In the study published in the magazine AstrobiologyUsing data from impact craters, Nish and her collaborators tried to determine how much organic molecules could be transported from Titan's organic-rich surface to its subsurface ocean.

Comets colliding with Titan throughout its history have melted the moon's icy surface, creating pools of liquid water that mixed with surface organic matter. The resulting melt is denser than its icy crust, so heavier water sinks through the ice, possibly reaching Titan's subsurface ocean.

Using assumed rates of impacts on Titan's surface, Nisch and her collaborators determined how many comets of different sizes would strike Titan each year over its history. This allowed researchers to predict the flow rate of water carrying organic materials moving from Titan's surface to its interior.

Nish and his team found that the weight of organic matter transported in this way is very small, no more than 7,500 kg per year of glycine – the simplest amino acid. sourWhich make up the proteins in life. This is approximately the same mass as a male African elephant. (All biomolecules, such as glycine, use carbon—an element—as the backbone of their molecular structure.)

“One elephant a year of glycine in an ocean 12 times the size of Earth’s oceans is not enough to sustain life,” Neesh said. “In the past, people often assumed that water equaled life, but they neglected the fact that life needs other elements, especially carbon.”

Other icy worlds (such as Jupiter's moons Europa and Ganymede and Saturn's moon Enceladus) have almost no carbon on their surfaces, and it is unclear how much can be obtained from within them. Titan is the most organic-rich icy moon in the solar system, so if the ocean beneath its surface is uninhabitable, it doesn't bode well for other known icy worlds.

“This work shows that it is very difficult to transport carbon on Titan's surface to its subsurface ocean, and it is very difficult for the water and carbon needed for life to coexist in the same place,” Nisch said.

Dragonfly is a quadcopter lander that will take advantage of the environment on Titan to fly to multiple locations, hundreds of miles apart, to sample materials and determine surface composition to investigate Titan's organic chemistry and habitability, and to monitor atmospheric and surface conditions. Topography for studying geological processes and conducting seismic studies. Credit: NASA

Dragonfly flight

Despite this discovery, there is still a lot to learn about Titan, and for Nish, the big question is, what is it made of?

Nish is a co-investigator on NASA's Dragonfly project, a spacecraft mission planned for 2028 to send a robotic aircraft (drone) to the surface of Titan to study prebiotic chemistry, or how organic compounds formed and self-organized for the origin of life. On and off the ground.

“It is almost impossible to determine the composition of Titan's organic-rich surface by viewing it with a telescope through its organic-rich atmosphere,” Nish said. “We need to land there and take samples of the surface to determine its composition.”

So far, just that Cassini-Huygens International Space Mission In 2005, it successfully landed a robotic probe on Titan to analyze samples. This remains the first spacecraft to land on Titan and the farthest landing ever made by a spacecraft from Earth.

“Even if the subsurface ocean is not habitable, we can learn a lot about the chemistry of pre-life on Titan, and Earth, by studying interactions on Titan’s surface,” said Nisch. “We would really like to know if there are interesting interactions happening there, especially when organic molecules mix with liquid water resulting from collisions.”

When Nish began her final study, she was worried that it would negatively impact the Dragonfly mission, but it actually led to more questions.

“If all the melting from the impacts sank into the ice crust, we wouldn't have samples near the surface where water and organic matter mix,” Nish said. “These are the areas where Dragonfly can look for the products of those prebiotic reactions, to teach us how they might have arisen.” Life on different planets.

“The results of this study are more pessimistic than I realized regarding the habitability of Titan's surface ocean, but they also mean that more interesting prebiotic environments exist near Titan's surface, which we can sample using instruments on Dragonfly.”

Reference: “Organic inputs to Titan's subsurface ocean through impact craters” by Katherine Nish, Michael J. Malaska, Christophe Soutine, Rosalie M. C. Lopez, Connor A. Nixon, Antonin Affolder, Audrey Chattin, Charles Cockell, Kendra K. Farnsworth, Peter M. Higgins, Kelly E. Miller and Christa M. Soderlund, February 2, 2024, Astrobiology.

doi: 10.1089/ast.2023.0055

“Beer aficionado. Gamer. Alcohol fanatic. Evil food trailblazer. Avid bacon maven.”