Edward “Ned” Johnson III, who turned Fidelity Investments into a financial giant and opened Wall Street to millions of Americans, died Wednesday. Mr Johnson was 91 years old.

“He passed away peacefully at his Florida home in the midst of his family,” Abigail Johnson, who succeeded her father as CEO of Fidelity in 2014 and chair of the board in 2016, wrote on LinkedIn Thursday.

A Fidelity spokeswoman said Mr Johnson died of natural causes in Wellington, Florida, where he had lived all the time in recent years.

Mr. Johnson inherited the famed Boston Corporation from his father in the 1970s, as investors were grinding into a bear market that would dampen enthusiasm for the market and sell off Fidelity mutual funds. While many of Fidelity’s competitors have collapsed, Mr. Johnson has pushed the company to reshape itself with a series of new projects.

Fidelity was the first to introduce a money market fund that allows investors to write checks on their holdings. The company created a toll-free number and advertised it. (Mr. Johnson even helped write the ad copy.) Fidelity opened its own discount brokerage, increasing its reach among individual investors, and expanding overseas. Under Mr Johnson’s direction, Fidelity has also built the largest 401(k) company in the country, helping millions save for retirement.

His enthusiasm for stocks—and his talent for marketing executives like Peter Lynch—helped rekindle many Americans’ love affair with the market.

“Fidelity would have stagnated if Ned had not come along and set up an entirely new business,” said Joshua Berman, a longtime legal advisor to Mr Johnson.

Several initiatives also represent what may be the most enduring legacy of Mr. Johnson, according to executives who worked with him: “He wanted to take the investment tools available to his social class and spread them across the middle class,” said Robert Posen. , former Fidelity chief.

Fidelity ended 2021 with $11.78 trillion in assets under management, or what’s in Fidelity’s accounts as well as Fidelity money held by competitors’ clients. The company’s total assets under management, or the amount supervised by Fidelity funds, was $4.48 trillion, up from $3.8 trillion a year earlier.

Fidelity has grown into a financial giant but has remained, like Mr. Johnson himself, a very private person. The Johnsons control 49% of FMR Corp, Fidelity’s mother.

Boston’s richest man lived for nearly half a century in the same Beacon Hill townhouse, which is a short walk from the old Fidelity offices on Devonshire Street. He applied to dozens of institutions that supported the arts and medical research, but no museums, hospitals, or art libraries bear his name.

Mr. Johnson shared his father’s fascination with Asian culture, spending a month or more each year on a trip through Japan or China.

The younger Mr. Johnson was an important art collector, with a particular interest in New England furniture. For years, he carried a flashlight to check the carpentry of any Chippendale he came across.

Mr. Johnson and his daughter Abigail Johnson in 2004.

Photo:

Brooks Craft/Corbis/Getty Images

He founded the Brookfield Arts Foundation, which owned several hundred ancestral clocks, and once had an entire two-story house that was dismantled in China and moved, in more than 2,000 pieces, to a museum in Salem, Massachusetts.

“He was a very extraordinary man,” said legal counsel Mr. Berman. “He was passionately curious about anything.”

Mr. Johnson is survived by his wife Elizabeth, his three children Abigail, Elizabeth and Edward, and seven of his grandchildren.

“He loved his family, co-workers, work, stock market, arts and antiquities, tennis, skiing, sailing, history, and good debate,” Abigail Johnson wrote. “He can be counted on to have a conflicting view on anything.”

Edward Crosby Johnson III was born in 1930. He grew up in the Brahmin area of Milton, Massachusetts, in the home where his grandmother raised her family.

The Johnson family, who can trace their roots in Boston to the seventeenth century, had wealth and prestige long before Mr. Johnson’s father, a lawyer by training, founded Fidelity in 1946. But Edward Johnson II loved the stock market and all its imperfections, and he He imbued his son with the same magic all his life.

“We’re learning a lot about brokering, but don’t say that to Ned,” Edward Johnson once told his aide after outing with his young son, according to a Boston Magazine article.

His classmates and colleagues said the younger Johnson struggled with dyslexia, and moved through several middle schools before heading to Harvard College.

“The reading has been very difficult for him,” said James Kervey, former president of Fidelity. “But it was very visual.”

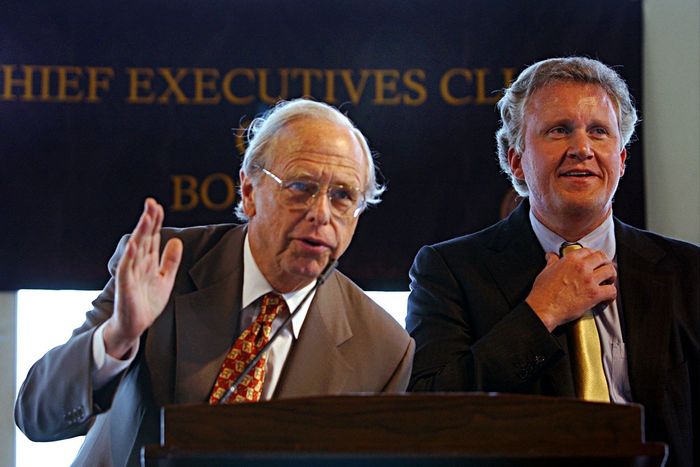

Ned Johnson, left, with General Electric CEO Jeffrey Immelt, in 2002.

Photo:

Chitose Suzuki/Press Auxiliary

In his meetings with his aides, Mr. Johnson would take apart the staplers and reassemble them. Years later, when he struggled to explain how he wanted Fidelity’s first site to appear, he cleared his calendar and spent six weeks working alongside the company’s software engineers, Curvey said.

Mr Johnson spent two years in the army before returning to Boston for a brief period

State Street corp.

Mr. Johnson joined his father’s firm in 1957 as an analyst working for Gerald Tsai, then Fidelity’s first director.

By the 1960s, Mr. Johnson’s investments began to outperform other growth funds – including Mr. Tsai’s. When Fidelity launched its flagship fund of the future,

Magellan’s fidelityin 1963, Mr. Johnson was its first director.

In 1972, when Mr. Johnson became president of the company, Fidelity was managing $3.9 billion in assets — mostly in stock funds that would run out of money until the market began to recover a decade later.

Fidelity made its first direct contact with Main Street in 1974 with the launch of the New Money Market Fund. The company launched its brokerage business in 1978, and in 1982 it began selling retirement accounts to American companies. In 1995, Fidelity became the first major investment company with a website.

The steps would also herald sweeping changes in the way Americans invest. Fidelity has tapped into the category of self-motivated investors who don’t need intermediaries to tell them where to put their money.

Mr. Johnson has invested heavily in technology, installing generators under the piers of the Fidelity office tower to ensure the company does not lose power. He rarely avoids sharing his opinions with tech dignitaries like

Microsoft corp.

Co-founder Bill Gates, according to former Fidelity chief Bob Reynolds.

Mr Johnson has also tangled – usually behind the scenes – with politicians over taxes. As Fidelity expanded, it sought to move businesses and employees to offices outside of its home state. He left his family office for the more lenient tax laws in New Hampshire.

For Mr Johnson, thoughts flowed in a choppy rhythm. Some worked, others failed. Fidelity was a family business—there were no general shareholders or quarterly reports to limit his horizon or imagination, and there were fewer critics to condemn the company’s gaffes.

“I don’t think there was ever a strategic plan,” said Peter Lynch, Fidelity’s star manager once.

Mr Johnson would frequently visit Mr. Lynch’s office to pick his brain, always, at the end of the day. “I had a code,” said Mr. Lynch. “I’d call my wife and ask, ‘What’s for dinner?'” “That means Mr. Lynch will miss the 6:15 p.m. train, perhaps more than that.

The conversation went on for decades. “Now we’re talking about Tesla, or

an AppleAnd the

“It’s the same question he would have asked 50 years ago,” Mr. Lynch said in 2018.

Mr. Johnson’s father died in 1984. “I’ve never seen a father and son so close together,” said Mr. Reynolds. He would go to his father’s office and spend four hours there. All they will do is talk about the market.”

Abigail, Mr. Johnson’s daughter, joined Fidelity in 1988.

She climbed steadily, eager to put her own stamp on devotion. In 2004, Ms Johnson sought to have her father removed from office due to disagreements with some business decisions. People familiar with the matter said the plan failed after he learned of it and released enough stock to reduce his children’s ownership of the family business.

After the dust was over, people said, he formed a three-person committee to address the company’s succession plan. Another decade would pass before Johnson was ready to hand the job over to his daughter.

The market’s rise in the wake of the financial crisis has left many investors frustrated with the returns of active funds, and the high fees they have charged. Set in full swing, Fidelity has been on the back burner as the industry shifts toward low-cost index funds. Mr Johnson was reluctant to accept the looming changes. He eventually did, launching index funds and offering passive funds to others for brokerage clients, but “I don’t think he ever believed in them,” Mr. Reynolds said.

After his retirement, Johnson has stayed out of the spotlight.

“I am proud of what we have built, and equally proud of what Fidelity has become,” Johnson said in a January 2022 statement to the Wall Street Journal. “The focus has been on our customers since day one, and that’s true today.”

At a 2012 dinner honoring the Johnson family, Mr. Johnson watched his daughter recount the family dinner interrupted by Fidelity agents. She said her father always took those calls.

“He was an all-consuming man with endless passion and energy to fix things,” said Ned Johnson.

write to Justin Baer at [email protected]

Copyright © 2022 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. all rights are save. 87990cbe856818d5eddac44c7b1cdeb8

“Beer aficionado. Gamer. Alcohol fanatic. Evil food trailblazer. Avid bacon maven.”