Black workers have led the US’s return to work after the Covid crisis, but economists warn their gains will reverse as the Federal Reserve aggressively tries to cool the economy. Interest rate He increases.

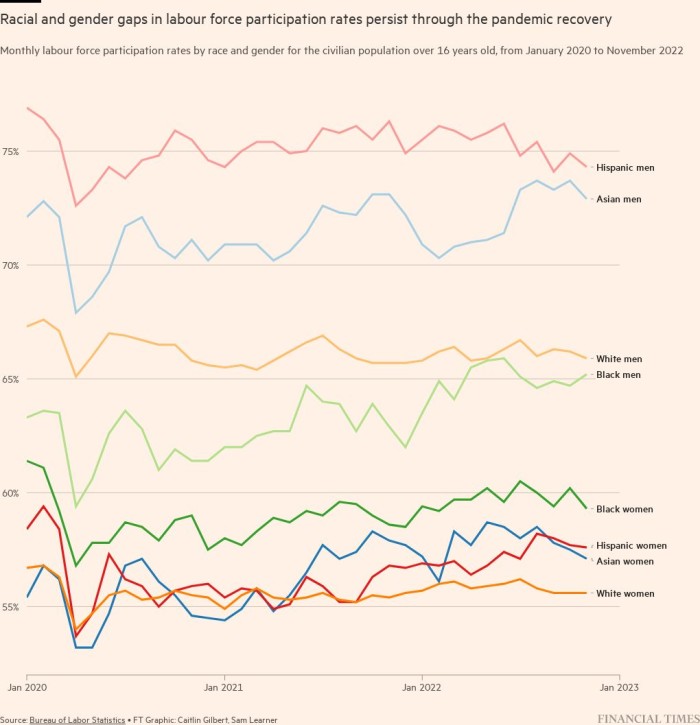

Earlier this year, rising wages and a shortage of workers pushed black workers into the job market at record levels. Black Americans worked and looked for jobs at higher rates than white Americans in May for the first time since 1972, according to Labor Department data. Employers have lowered job requirements, expanded skills improvement programs and diversified their hiring plans to fill their ranks amid staffing shortages, offering new opportunities to historically disadvantaged workers in the process.

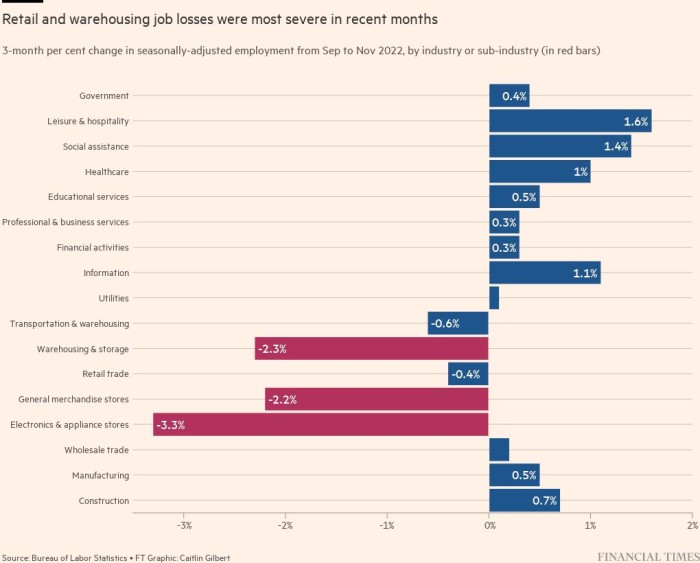

While unemployment and labor force participation rates for workers of color have remained relatively stable in recent months, rising interest rates and a deteriorating job market could reverse those gains. In recent months, employment has already fallen in several industries that disproportionately employ workers of color, including retail, transportation, and warehousing.

Between September and November, general merchandise stores, including department stores, lost 71,500 jobs, and the warehouse and warehousing industry lost 41,000 jobs. Many of these industries rely on low-wage workers, with average annual wages often in the $30,000 to $50,000 range in retail and warehousing.

William Spriggs, professor of economics at Howard University and chief economist for the AFL-CIO, said, “The moment companies stop hiring . . . the unemployment rate goes up because unemployed people can’t escape unemployment. And that hurts black workers first.”

Spriggs added that the “significant uptick in black labor force participation, which has really helped black workers in the last six months…that goes a long way.”

Concerns about the US economy tipping into recession faded as the Federal Reserve continued its most aggressive series of interest rate hikes since the early 1980s. In an effort to tackle decades-high inflation, the central bank in less than a year raised its benchmark policy rate from nearly zero as of March to roughly 4.5 percent currently. Interest rates are expected to rise next year, with senior officials forecasting the federal funds rate to peak at 5.1 percent.

Policymakers believe there is a way for inflation to return to the Fed’s 2 percent target without massive job losses and a recession – the claim of many economists across Wall Street and academia. Modern survey Conducted by the Financial Times in partnership with the University of Chicago Booth School of Business, it found that the vast majority of leading economists expect a recession next year, which they warn could push the unemployment rate beyond 5.5 percent from the current 3.7 percent.

Most Fed officials currently expect the unemployment rate to rise by about one percentage point to 4.6 percent next year and to remain at that level through the end of 2024.

Economists and policymakers acknowledge this people of color They are disproportionately affected when the unemployment rate is high, especially when there is a recession, even if it is mild.

“Black Americans don’t have low unemployment rates,” says Algernon Austin, director of race and economic justice at the Center for Economics and Policy Research, a Washington-based think tank. “The unemployment rate ranges from high to very high to very high.”

“It is important to realize that a mild recession means a transition from a high unemployment rate to a very high unemployment rate for blacks.”

Before the pandemic — when the US labor market was healthy — the unemployment rate for black Americans was twice the unemployment rate for white and Asian adults. In 2019, it was 6.1 percent, compared to just 3.3 percent and 2.7 percent for white and Asian adults, respectively. For Hispanic adults, the rate was 4.3 percent.

At the worst of the Covid economic crisis, the black unemployment rate jumped to nearly 17 percent. For white workers, it was slightly lower, at 14 percent.

Federal Reserve officials emphasized that inflation is also affecting those communities the most, and that in order to return to a healthy economy, they must restore control of prices. They argue that failure to do so in the near term will mean more pain later, as the central bank will have to squeeze the economy even harder.

“Without price stability, the economy doesn’t work for anyone,” Jay Powell, chairman of the Federal Reserve, said in mid-December at his last press conference of the year. “We will not achieve a sustainable period of strong labor market conditions that benefit everyone.”

Austin expressed concerns about other factors, such as the war in Ukraine and China’s Covid policy, which are outside the Fed’s control but have a significant impact on the path of inflation. He warned that the central bank was not only “unnecessarily” imposing costs on the most economically vulnerable, it was also reducing their ability to deal with price pressures they were already struggling to overcome.

“[Put] If people are unemployed, they will not be able to deal with inflation.

“Beer aficionado. Gamer. Alcohol fanatic. Evil food trailblazer. Avid bacon maven.”