All eyes are on the source of the record-breaking gamma-ray burst that lit up the sky last week.

On October 9, a beam of light more energetic than astronomers have ever seen passes through our planet, temporarily blinding the detectors on several NASA satellites. The ray came from a gamma ray burstIt is the most active type of explosion known to occur in Universe (part of the the great explosion) which is believed to accompany the birth of some black holes.

Within hours, dozens of telescopes around the world were pointing in the direction of the source of the explosion, confirming that this, indeed, was one of the books. The event, officially named GRB221009Ahas since earned the nickname BOAT (“the brightest of all time”), and astronomers hope it will help shed light on the mind-boggling physics behind these disastrous phenomena.

“It’s an event that happens once every century, maybe once every 1,000 years,” Brendan O’Connor, an astronomer at the University of Maryland and George Washington University told Space.com. “We are really in awe of this event and feel very lucky to be able to study it.”

Related: A study has found that gamma-ray bursts may be much rarer than we thought

Gamma ray bursts are not rare. About once a day, one flashes briefly on our planet from somewhere in the universe. Many events are believed to occur throughout the universe. Some gamma ray bursts glow for a fraction of a second, possibly caused by collisions neutron starswhich are astral corpses left after that Supernova Huge explosions stars whose heart ran out of fuel. Others can last for several minutes, most likely when a black hole, just born from a supernova explosion, swallows so much of its parent star at once that it has to dump some of it in a very powerful jet.

The October 9 gamma-ray burst stood out even among previously observed long-range gamma-ray bursts, as its photons bombarded satellite detectors for about 10 minutes. The energy packed into those photons was higher than any energy ever measured. At 18 TeV, at least some of the GRB221009A photons outnumbered by a factor of two the most energetic particles produced by the most powerful particle generator on Earth, Large Hadron Collider.

The afterglow of the explosion caused by the interaction of gamma rays with cosmic dust was also out of the ordinary, outstripping any other auroras seen before despite the fact that GRB221009A emanated from a part of the sky obstructed by the thick band of Milky Way galaxy. The explosion was so powerful that it ionized Earth’s atmosphere Long-wave radio communications were disrupted.

O’Connor, who was part of a team of astronomers who used the Gemini South telescope in Chile to observe the effects of GRB221009A in October, said astronomers were able to trace the origin of only about 30% of all gamma-ray bursts tearing the Earth in October. 14, about a week after it first lit. In the case of GRB221009A, astronomers have found the source: a dust-filled galaxy in the constellation Sagitta, also known as Arrow. Then came another surprise: a gamma-ray burst occurred much nearer a land Than most others have seen before.

“These gamma-ray bursts come from the collapse of massive stars, and these stars have very short lives,” Northwestern University astronomy student Jillian Rastingad, who took part in the Gemini South measurements, told Space.com. “These stars trace the history of star formation in the universe. Therefore, as star formation reaches its peak, long gamma-ray bursts reach their peak, which is approximately half the life of the universe. However, this gamma-ray burst occurred recently, much closer to us” .

Astronomers estimate that the source of GRB221009A lies at about 2.4 billion light years from Earth. Closer gamma-ray bursts had been observed before, but they were not as active as GRB221009A, which added to the event’s special status.

“Because this event looks so bright to us, we’ll be able to study it longer and in much better detail,” O’Connor said. “At least 50 telescopes are now looking at it in all wavelengths, and this will help us maximize science.”

Although gamma-ray bursts only last for a few short minutes at best, they produce observable effects for weeks. Astronomers are also looking for the supernova that triggered the explosion, which expels material outward more slowly.

“Our current understanding of these explosions is that you have a massive star, and when it collapses, it creates a black hole, into which then some material falls from the star,” O’Connor said. “The black hole then spits it out as this flux, which is moving at nearly the speed of light, a gamma-ray burst. At the same time, when a star explodes, some of this material bounces outward, essentially starting to move away at much slower speeds, but no It’s still very fast. And that’s a supernova explosion.”

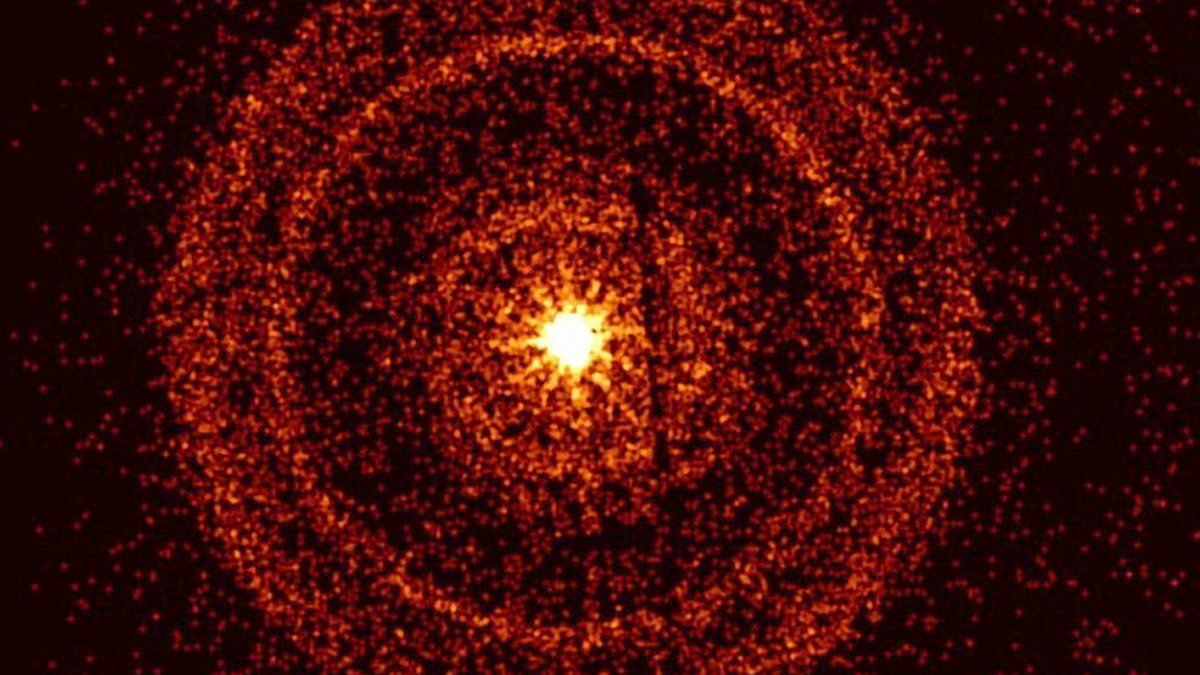

When the gamma rays of the initial burst interact with material in the surrounding universe, they produce the afterglow, which, Rastingad said, spans the electromagnetic spectrum but is best observed in X-rays and radio wavelengths. Astronomers are still observing the afterglow of GRB221009A, which was first captured NASA’s Swift satellite hunting for gamma rays The formation of colored rings around the source in the first hours after the explosion.

Rastingad said telescopes are now beginning to see the first signs of the supernova explosion that gave rise to GRB221009A, and he expects it to “fully develop” over the next few weeks. However, due to the location of the explosion source in the sky, they would not be able to observe the supernova throughout its life span of several months.

“It’s starting to swing behind the sun. So by about the end of November we won’t be able to watch it until February,” Rastingad said.

At that time, O’Connor hoped, NASA James Webb Space Telescope And the Hubble Space Telescope She will join this effort, and her superior power in optical and infrared observation contributes to the effort.

“This is a great opportunity to research how much mass has been created [in that event]”But also to understand what chemical elements were created in this event. We still don’t know how some of the heaviest elements in the universe were formed, and we think we might be able to see such processes in supernova explosions,” Rastingad said.

Gamma-ray bursts were discovered by chance in the 1960s by US military satellites developed to monitor Soviet nuclear tests (which also produce gamma rays), and they remained a complete mystery for decades. It was only in the 1990s that astronomers first realized that these powerful flashes of light from all corners of the universe might have something to do with collapsing giant stars.

However, much of the current understanding of gamma-ray bursts still relies on theory and computer modeling, rather than observations, and astronomers hope that GRB221009A will help fine-tune those theories. A slew of research papers on all aspects of this carefully observed event are sure to follow in the coming months as astronomers strive to make the most of this once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.

While the relative proximity of a burst with the force of GRB221009A is a boon to science, astronomers aren’t keen on seeing a gamma-ray burst near Earth. Especially in our galaxy. Scientists believe that a gamma-ray burst targeting our planet from a distance of thousands of light-years would destroy the planet’s protective ozone layers and lead to changes in the atmosphere that could lead to the Ice Age. In fact, one of these gamma-ray bursts may have triggered one of the five major extinction events in Earth’s history, the Ordovician mass extinction about 440 million years ago.

“Fortunately, the jets that cause gamma-ray bursts are fired very narrowly,” O’Connor said. “Only a few degrees displayed. But if it happened in our galaxy and was pointed at us, it would be really dangerous for us. Fortunately, the rate of these events that we expect to happen in each galaxy is incredibly low.”

Follow Teresa Poltarova on Twitter Tweet embed. Follow us on Twitter Tweet embed and on Facebook.

“Beer aficionado. Gamer. Alcohol fanatic. Evil food trailblazer. Avid bacon maven.”