In 2009, a giant star 25 times more massive than the Sun disappeared.

Well, it wasn’t that simple. It went through a period of brightness, increasing in luminosity to a million suns, just as if it was ready to explode into a supernova.

But then it fizzled out instead of exploding. When astronomers tried to view the star using the Large Binocular Telescope (LBT), Hubble and the Spitzer Space Telescope, they couldn’t see anything.

The star, known as N6946-BH1, is now considered a failed supernova. The name BH1 is due to the fact that astronomers believe the star collapsed into a black hole rather than sparking a supernova. But that was a guess.

All we know for sure is that it brightened for a while and then became too dim for our telescopes to detect. But that changed thanks to the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST).

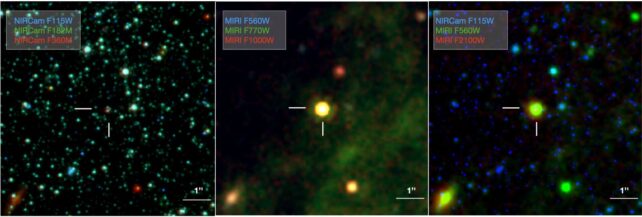

new study, Published on arXiv, analyzes data collected by JWST’s NIRCam and MIRI instruments. It shows a bright infrared source that appears to be the remains of a dust crust surrounding the location of the original star. This would be consistent with material being ejected from the star as it brightens rapidly.

It is also possible that it is an infrared glow from material falling into the black hole, although this seems less likely.

Surprisingly, the team also found the remains of not one object, but three.

This makes the failed supernova model less likely. Previous observations of N6946-BH1 were a combination of these three sources because the resolution was not high enough to distinguish them.

So the most likely model is that the brightening that occurred in 2009 was due to the merger of stars. What looked like a bright, massive star was a star system that brightens when two stars merge and then fades away.

While the data leans toward the merger model, it cannot rule out the failed supernova model. This makes our understanding of supernovae and stellar-mass black holes more complex.

We know from black hole mergers observed by LIGO and other gravitational wave observatories that stellar-mass black holes exist and that they are relatively common. So some massive stars become black holes.

But whether they would have become supernovas to begin with is still in question. Ordinary supernovae can have enough mass to become a black hole, but it is difficult to imagine how the largest stellar black holes could form after supernovae.

N6946-BH1 is located in a galaxy 22 million light-years away, so the fact that the James Webb Space Telescope can distinguish between multiple sources is impressive. It also gives astronomers hope of observing similar stars in time.

With more data, we should be able to distinguish between stellar mergers and true failed supernovae, which will help us understand the final stages of stars as they move toward becoming stellar-mass black holes.

This article was originally published by The universe today. Read the Original article.

“Beer aficionado. Gamer. Alcohol fanatic. Evil food trailblazer. Avid bacon maven.”