The pioneering discovery of a 550-million-year-old marine sponge fossil provides new insights into sponge evolution and directs future fossil research. Reconstruction of the life site of Helicolossus on the Ediacaran sea floor. Credit: Yuan Xunlai

The research provides new insights into the early evolution of animals.

Researchers led by Shuhai Xiao at Virginia Tech have discovered a 550-million-year-old marine sponge fossil, highlighting a 160-million-year gap in the fossil record. This fossil, which suggests that early sponges lacked mineral skeletons, provides new insights into the evolution of one of the oldest animals and influences how paleontologists search for ancient sponges.

At first glance, the simple sea sponge does not seem like a mysterious creature. No brain. No gut. No problem with it dating back 700 million years. However, the convincing sponge fossils date back only about 540 million years, leaving a gap of 160 million years in the fossil record.

In a paper published June 5 in the journal natureVirginia Tech geobiologist Shuhai Xiao and his collaborators reported on a 550-million-year-old marine sponge of “lost years” and suggested that even older marine sponges had not yet evolved mineral skeletons, providing new criteria for searching for lost fossils.

The mystery of the disappearance of sea sponges revolves around a paradox. Molecular clock estimates, which involve measuring the number of genetic mutations that accumulate over time, suggest that sponges must have evolved about 700 million years ago. However, no convincing sponge fossils have been found in rocks that old.

For many years, this mystery has been the subject of debate among zoologists and paleontologists.

This latest discovery fills in the evolutionary family tree of one of the oldest animals, explaining their conspicuous absence in ancient rocks and connecting the dots to Darwin’s questions about when they evolved.

Xiao’s pioneering discovery

Xiao, recently appointed to the National Academy of Sciences, first saw the fossil five years ago, when a collaborator sent him a photo of a specimen excavated along the Yangtze River in China. “I’ve never seen anything like this before,” said Xiao, a faculty member in the College of Science. “Almost immediately, I realized it was something new.”

Xiao and his colleagues from the University of Cambridge and the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Paleontology began ruling out possibilities one by one: no sea squirt, no sea anemone, and no coral. Could it be an elusive ancient sea sponge, they wondered?

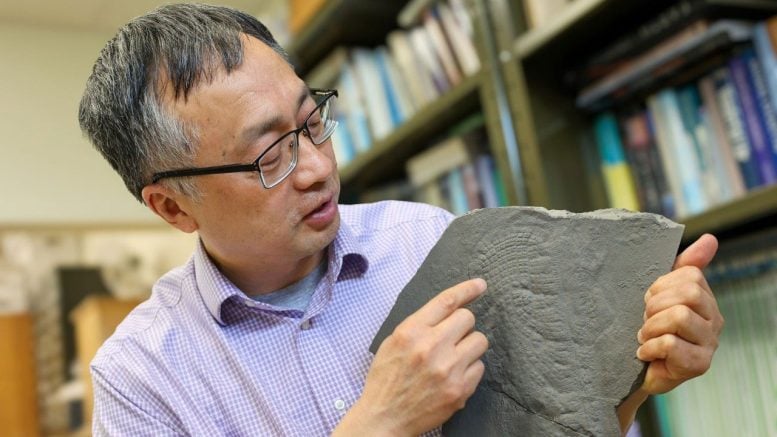

Shuhai Xiao, a geobiologist at Virginia Tech, and his colleagues reported a 550-million-year-old marine sponge fossil, filling a gap in the evolutionary family tree of one of the oldest animals. Photo by Spencer Coppage for Virginia Tech. Credit: Spencer Coppage for Virginia Tech

In a previous study published in 2019, Xiao and his team suggested Early sponges left no fossils because they did not evolve the ability to generate the hard, needle-like structures, known as spicules, that characterize marine sponges today.

Members of Xiao’s team traced the evolution of sponges through the fossil record. As they moved back in time, the sponges’ spicules became more organic in composition and less mineralized.

“If you extrapolate, the first creatures were probably soft-bodied creatures with completely organic skeletons and no minerals at all,” Xiao said. “If this is true, they would only be able to survive fossilization under very special conditions where rapid fossilization trumps decomposition.”

Later in 2019, Xiao’s international research team found a sponge fossil preserved in such conditions: a thin layer of marine carbonate rock known to preserve an abundance of soft-bodied animals, including some microorganisms. The oldest mobile animals.

“More often than not, this type of fossil is lost in the fossil record,” Xiao said. “The new discovery provides a window into early animals before they develop into solid parts.”

New fossil discovery and its implications

The surface of the new sponge fossil is studded with a complex array of regular boxes, each divided into smaller, identical boxes.

“This specific pattern suggests that our fossilized sea sponges are most closely related to a particular species Classify “It’s made of glass sponge,” said Xiaoping Wang, a postdoctoral researcher at the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Paleontology and the University of Cambridge.

Another unexpected aspect of the new sponge fossil is its size. “When looking for early sponge fossils, I expected them to be very small,” said collaborator Alex Liu from the University of Cambridge. “The new fossil is about 15 inches long with a relatively complex conical body plan, which challenges many of our expectations about the appearance of early sponges.”

While the fossil fills in some missing years, it also provides researchers with important guidance on how to look for these fossils — which will hopefully expand understanding of early animal evolution later on.

“The discovery suggests that the first sponges may have been spongy but not glassy,” Xiao said. “We now know that we need to broaden our view when searching for early sponges.”

Reference: “A Sponge Fauna from the Late Ediacaran Crown Group” by Xiaoping Wang, Alexander J. Liu, Zhi Chen, Chengxi Wu, Yarong Liu, Bin Wan, Qi Pang, Quanming Zhou, Shunlai Yuan, and Shuhai Xiao, June 5, 2024, nature.

DOI: 10.1038/s41586-024-07520-y

“Beer aficionado. Gamer. Alcohol fanatic. Evil food trailblazer. Avid bacon maven.”