California-based Astra on Sunday launched two shoebox-sized NASA satellites from Cape Canaveral on a modest mission to improve hurricane forecasts, but the company’s second-stage low-cost booster malfunctioned before reaching orbit and the payloads were lost.

“The upper stage closed early and we did not deliver payloads to orbit,” Astra wrote on Twitter. “We have shared our regrets with NASA and the payload team. More information will be available after we complete our full data analysis.”

This was the seventh launch of the “Venture-class” Astra small rocket and the company’s fifth failure. Sunday’s launch was the first of three aircraft planned for NASA to launch six small CubeSats, two at a time, in three orbiters.

Given the somewhat precarious nature of relying on tiny shoebox-sized CubeAats and a rocket with a very short track record, the $40 million project requires only four satellites and a successful launch to achieve mission goals.

Webcast Astra / NASASpaceflight

The NASA contract calls for the last two flights by the end of July. Whether Astra can meet this schedule given the Sunday failure is not yet known.

“Although today’s launch with Astra did not go as planned, the mission provided a great opportunity for new science and launch capabilities,” NASA Chief Science Officer Thomas Zurbuchen tweeted.

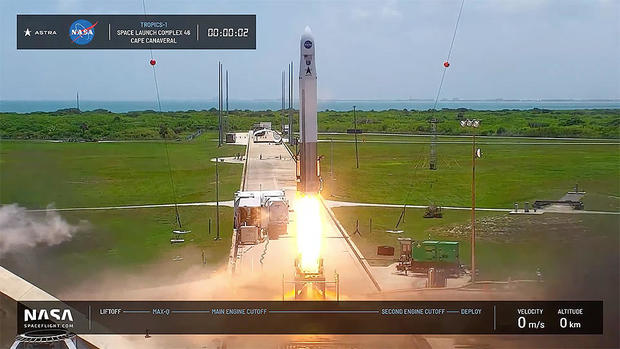

The launch came on Sunday and was delayed by 1 hour and 43 minutes, to ensure that the liquid oxygen fuel booster load was at the right temperature. Finally, hoping for the company’s third successful flight into orbit, Astra engineers counted down for takeoff at 1:43 PM ET.

With five first-stage engines generating 32,500 pounds of thrust, the 43-foot-high 3.3 blasted away from Panel 46 at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, making a dramatic show for area residents and tourists enjoying a sunny day nearby. beaches.

The first stage boosted the payload from the lower atmosphere, and was delivered to a single engine that powered the upper stage of the rocket.

Everything seemed to be running smoothly when, about a minute before the second-stage engine stopped, an onboard “rocket camera” showed a flash in the engine’s exhaust shaft. The camera view showed them what appeared to be a stumble before a video clip of the missile was cut.

Webcast Astra / NASASpaceflight

The goal of NASA’s TROPICS mission is to monitor the evolution of tropical storms in near real time by flying over hurricanes and other major systems every 45 to 50 minutes and sending back temperature, precipitation, water vapor and cloud ice data.

This rapid ability to revisit, that is, the time between satellite passages over a particular storm system, is intended to help scientists better understand how major storms develop and help forecasters better predict the storm’s path and intensity.

“It’s really hard to measure hurricanes coming from space, because they’re very dynamic, they change on minute time scales, and they need to resolve all the storm features, eyes, and rain bands spatially,” William said. Blackwell, principal investigator on the Tropis mission at MIT.

“Today, we probably have four or six hours before the next satellite flies. With the constellation Cubesat of six satellites… we can fly over it almost every hour. We will see how the storm changes, and we will be able to better predict how it might intensify.” What we are trying to do is improve our predictability.”

NASA is paying $8 million for three Astra launches, about $32 million to develop and test the cubes, and one year of data analysis.

The TROPICS mission presents more technical risks than NASA usually accepts — the cubes, while relatively inexpensive, have little repetition and Astra’s Rocket 3.3 has not demonstrated reliable performance — but officials say the potential scientific payoff justifies the “high-risk impact” project.

“I love TROPICS, just because it’s a kind of crazy job,” Zurbuchen said last week. “Think of six cubes… looking at tropical storms with repeating time 50 minutes instead of 12 hours.”

After Sunday’s failure, he tweeted: “Although we’re disappointed at the moment, we know: There is value in taking risks in NASA’s overall science suite because innovation is needed for us to lead.”

While the NASA contract covers six cubes and launchers, only four need to be operated to meet contract requirements. In this case, visit times would be around one hour, Blackwill said. With all six turned on, the gap between notes would be 45 to 50 minutes.

Placing TROPICS on what NASA calls a Venture-class rocket with a short trajectory record makes sense from a NASA perspective.

“You’re always nervous about any launch, no matter what the car is,” Blackwill said. But in this case, “we have the flexibility built in[in]to take on these kinds of new capabilities. So it’s a good match between our robust six-satellites mission, and you only need four, and this new low-cost, fast-release capability.”

“Beer aficionado. Gamer. Alcohol fanatic. Evil food trailblazer. Avid bacon maven.”