People say good things come to those who wait.[{” attribute=””>NASA thinks 50 years is the right amount of time as it begins tapping into one of the last unopened, Apollo-era lunar samples to learn more about the Moon and prepare for a return to its surface.

The sample is being opened at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston by the Astromaterials Research and Exploration Science Division (ARES), which safeguards, studies, and shares NASA’s collection of extraterrestrial samples. This work is being led by the Apollo Next Generation Sample Analysis Program (ANGSA), a science team who aim to learn more about the sample and the lunar surface in advance of the upcoming Artemis missions to the Moon’s South Pole.

Front from left, Drs. Ryan Zeigler, Rita Parai, Francesca McDonald, Chip Shearer and back left from left, Drs. Zach Sharp from the University of New Mexico and Francis McCubbin, Astromaterials Research and Exploration Science Division (ARES) astromaterials curator look on in excitement as gas is extracted into the manifold after the inner tube was pierced. Credit: NASA/James Blair

“Understanding the geologic history and evolution of the Moon samples at the Apollo landing sites will help us prepare for the types of samples that may be encountered during Artemis,” said Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator of NASA’s Science Mission Directorate in Washington. “Artemis aims to bring back cold and sealed samples from near the lunar South Pole. This is an exciting learning opportunity to understand the tools needed for collecting and transporting these samples, for analyzing them, and for storing them on Earth for future generations of scientists.”

When Apollo astronauts returned these samples around 50 years ago, NASA had the foresight to keep some of them unopened and pristine.

“The agency knew science and technology would evolve and allow scientists to study the material in new ways to address new questions in the future,” said Lori Glaze, director of the Planetary Science Division at NASA Headquarters. “The ANGSA initiative was designed to examine these specially stored and sealed samples.”

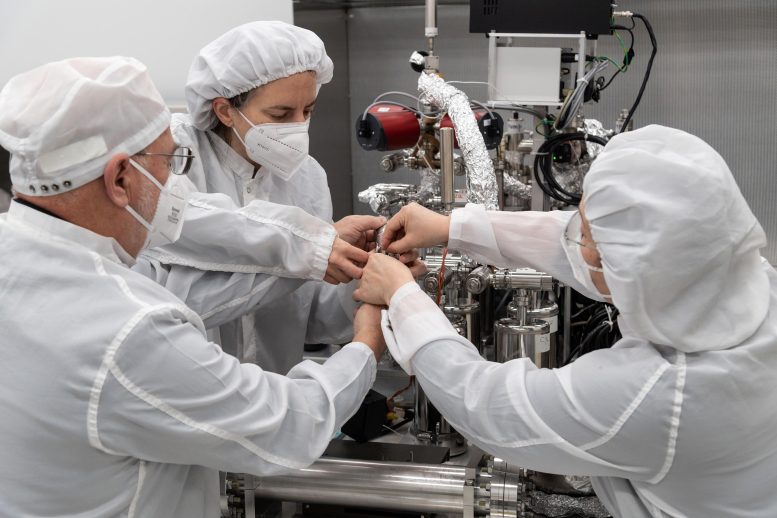

From left, Dr. Juliane Gross, Astromaterials Research and Exploration Science Division (ARES) deputy Apollo curator, alongside Drs. Alex Meshik, and Olga Pravdivtseva, from Washington University in St. Louis, begin a gas extraction process using the manifold. Credit: NASA

The ANGSA 73001 sample is part of an Apollo 17 drive tube sample collected by astronauts Eugene Cernan and Harrison “Jack” Schmitt in December of 1972. The astronauts hammered a pair of connected 1.5-by-14-inch tubes into the lunar surface to collect segments of rocks and soil from a landslide deposit in the Moon’s Taurus–Littrow Valley. The astronauts then individually sealed one drive tube under vacuum on the Moon before bringing them back to Earth; only two drive tubes were vacuum sealed on the Moon in this way, and this is the first to be opened. The other half of this drive tube, 73002, was returned in a normal (unsealed) container. The sealed tube has been carefully stored in a protective outer vacuum tube and in an atmosphere-controlled environment at Johnson ever since. The unsealed segment was opened in 2019 and revealed an interesting array of grains and smaller objects, known as rocklets, that lunar geologists were eager to study.

Now, scientists are focusing attention on the sealed, lower segment of the core. The temperature at the bottom of the core was incredibly cold when it was collected, which means that volatiles (substances that evaporate at normal temperatures, like water ice and carbon dioxide) might have been present. They are particularly interested in the volatiles in these samples from the equatorial regions of the Moon, because they will allow future scientists studying the Artemis samples to better understand where and what volatiles might be present in those samples.

From left, Dr. Juliane Gross, Astromaterials Research and Exploration Science Division (ARES) deputy Apollo curator, and Dr. Francesca McDonald, from ESA, take precise measurements from the piercing device prior to using the newly developed tool. Credit: NASA/James Blair

The amount of gas expected to be present in this sealed Apollo sample is likely very low. If scientists can carefully extract these gases, they can be analyzed and identified using modern mass spectrometry technology. This technology, which has evolved to levels of extreme sensitivity in recent years, can precisely determine the mass of unknown molecules and use that data to precisely identify them. This not only makes for improved measurements, but also means the collected gas can be divided into smaller portions and shared with more researchers conducting different kinds of lunar science.

NASA’s Ryan Zeigler, the Apollo sample curator, is overseeing the process of extracting the gas and rock. It’s also Zeigler’s job to properly prepare, catalog, and share the sample with others for research.

“A lot of people are getting excited,” said Zeigler. “University of New Mexico’s Chip Shearer proposed the project over a decade ago, and for the past three years, we’ve had two great teams developing the unique equipment to make it possible.”

The device being used to extract and collect the gas, called a manifold, was developed by Drs. Alex Meshik, Olga Pravdivtseva, and Rita Parai from Washington University in St. Louis. Dr. Francesca McDonald from the European Space Agency led a group in building the special tool to carefully pierce the container holding the lunar sample without letting any gas escape. Together, they’ve created and rigorously tested a one-of-a-kind system to collect the extremely precious material – gas and solid – that is sealed inside the containers.

On, February 11, the team began the careful, months-long process to remove the sample by first opening the outer protective tube and capturing any gas inside. Zeigler and his team knew what gases should be present inside the outer container and found everything was as expected. The tube seemed to contain no lunar gas, indicating the seal on the inner sample tube was still likely intact. On February 23, the team began the next step: a multi-week process of piercing the inner container and slowly gathering any lunar gases that are hopefully still inside.

After the gas extraction process is finished, the ARES team will prepare to carefully remove the soil and rocks from their container, likely later this spring.