The body is very good at repairing itself, but some parts of our anatomy struggle to return to normal after injury.

One such substance is cartilage—the spongy but tough connective tissue that keeps our bones from rubbing and bumping into each other. Over time, the transparent or “glassy” components of cartilage can deteriorate significantly, leading to painful conditions such as Osteoporosis and chondromalacia.

Scientists have been working on finding a way to regenerate hyaline cartilage Years ago, a team from Northwestern University in the United States achieved a major breakthrough. They developed a biomaterial that is injected into damaged cartilage in living sheep, to act as a scaffold that promotes cartilage growth in active joints.

Cartilage is an essential component of our joints. Chemist Samuel Stubb says: From Northwestern University.

“When cartilage is damaged or broken down over time, it can have a significant impact on a person’s overall health and mobility. The problem is that cartilage in adult humans does not have an innate ability to heal. Our new treatment can stimulate repair in tissue that does not regenerate naturally. We believe our treatment could help address a serious, unmet clinical need.”

Cartilage deterioration is a major health problem. 2011 survey A study conducted in 18 countries showed that more than 1.3 million knee replacement surgeries are performed each year, and cartilage problems were the main factor.

Although there are other interventions that can help, such as creating microfractures to stimulate cartilage repair, these interventions often result in the growth of the wrong type of cartilage – tough, fibrous cartilage. fibrocartilage – loves cartilaginous scar tissue – Instead of the soft, flexible hyaline cartilage that covers the joints.

One potential treatment that scientists are working to improve is the use of scaffolds in cartilage defects that support the growth of hyaline cartilage. This has shown success in small mammals, such as mice, but fails in larger mammals, likely because of the greater stresses and forces that act on the joints of larger animals.

Stubb and his colleagues have developed a material that appears to solve this glaring problem. It’s a two-component biomaterial.

The first is a peptide molecule that binds to a protein called transforming growth factor beta-1which plays a crucial role in cell growth and division, especially in the skeleton, where it regulates the growth of bones and cartilage.

The second component is hyaluronic acidwhich you may know from your skin care products—it helps your skin stay soft by retaining moisture. It can also be found in joints and cartilage, where it acts as a lubricant, and plays a role in wound healing.

In test tube experiments, the researchers found that the hybrid material supported chondrogenic differentiation—the proliferation of cartilage cells, known as chondrocytes. They formed bundles of filaments, a natural structure found in skeletal muscle tissue.

Many research methods have reached the same point in the laboratory. The real test is whether this protein can withstand the effects of its effects on living animals, which can be applied to humans. Sheep are subjected to mechanical effects similar to those of humans, so the test was on sheep.

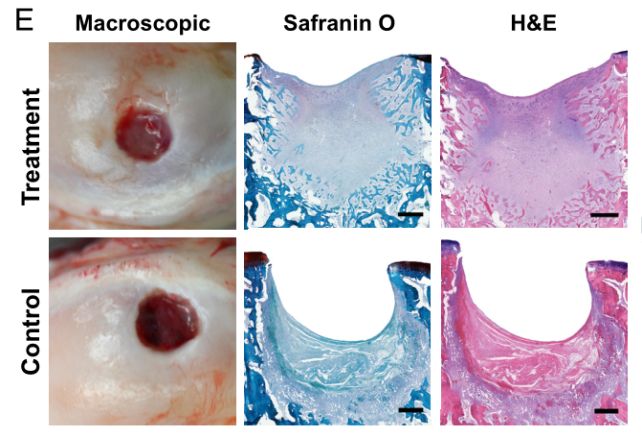

The researchers developed their substance into a paste that was injected into cartilage defects in the hind knee joints of sheep. The researchers made small holes in both hind knees of each of the sheep in their study; one knee was injected with the paste, and the other was left untreated as a control.

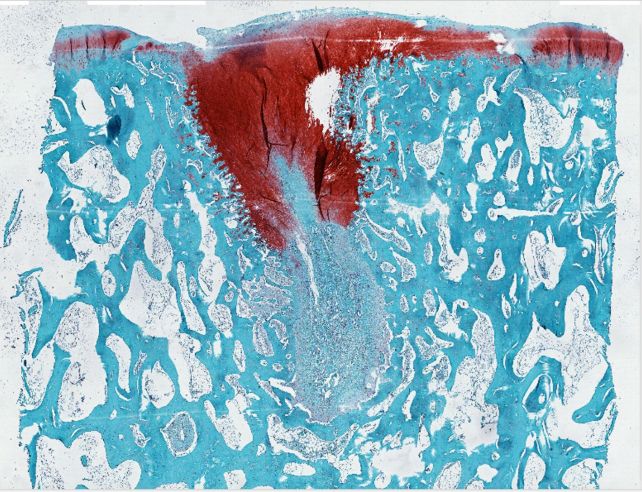

When the clay came into contact with the calcium in the sheep’s bones, it hardened into a rubbery matrix, and cartilage cells began to form, growing to fill the hole they had created as the scaffold deteriorated. The cartilage was of the right type: hyaline. Within weeks, the treated defects showed marked improvement, especially compared with controls.

A similar treatment may be more effective in humans. You can’t tell sheep that they need to rest and take their weight off their injured leg, whereas patients treated for cartilage injuries are often immobilized after surgery.

There is certainly more research and development to be done, and the procedure must then undergo clinical trials on humans. But the results suggest that the treatment will one day become available, which could help reduce the need for more invasive and less effective options.

“By regenerating hyaline cartilage,” Stop says“Our approach should be more resistant to wear and tear, correcting the problem of poor mobility and long-term joint pain while avoiding the need to reconstruct the joint with large pieces of hardware.”

The research was published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“Beer aficionado. Gamer. Alcohol fanatic. Evil food trailblazer. Avid bacon maven.”