Subscribe to CNN’s Wonder Theory newsletter. Explore the universe with news about amazing discoveries, scientific advances, and more..

CNN

—

Data from a retired NASA mission has revealed evidence of an underground reservoir of water deep beneath the surface of Mars, according to new research.

A team of scientists estimates that the water trapped in tiny cracks and pores in the rocks in the middle of the Martian crust could be enough to fill oceans on the planet’s surface. The study found that groundwater likely covers the entire surface of Mars to a depth of one mile (1.6 kilometers).

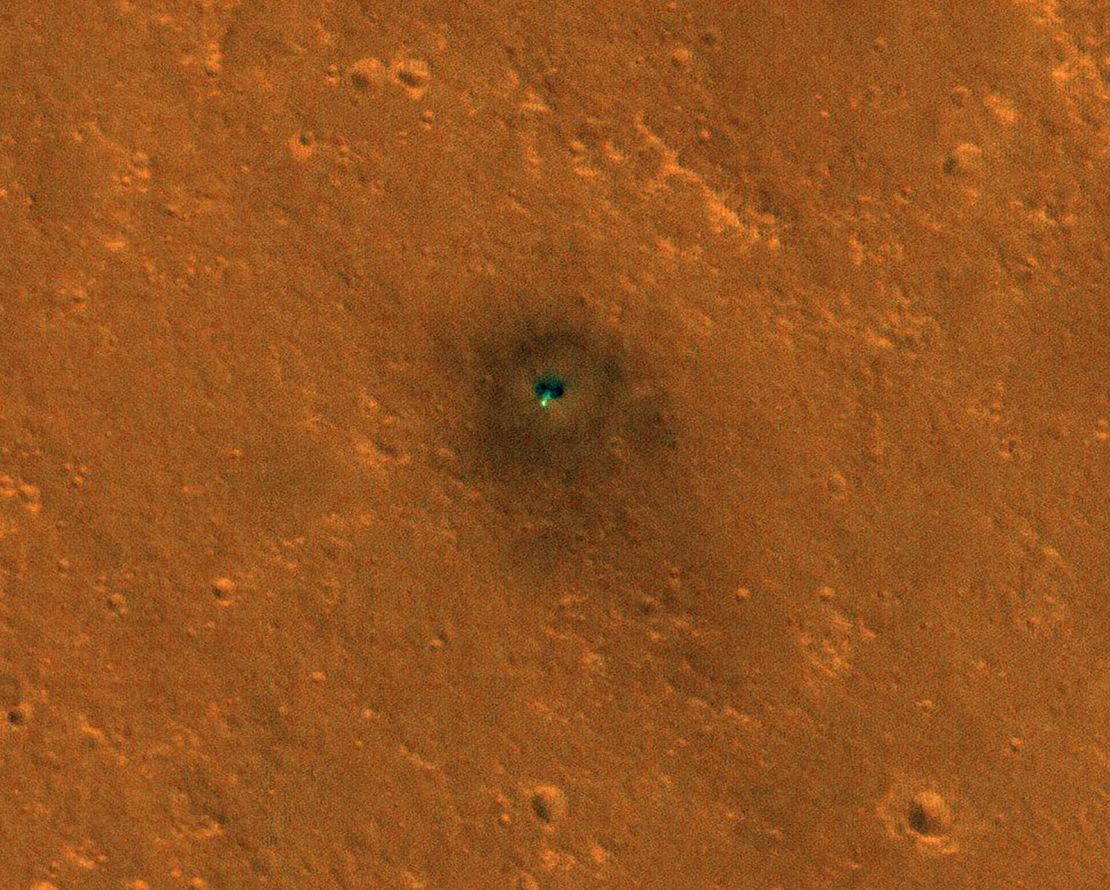

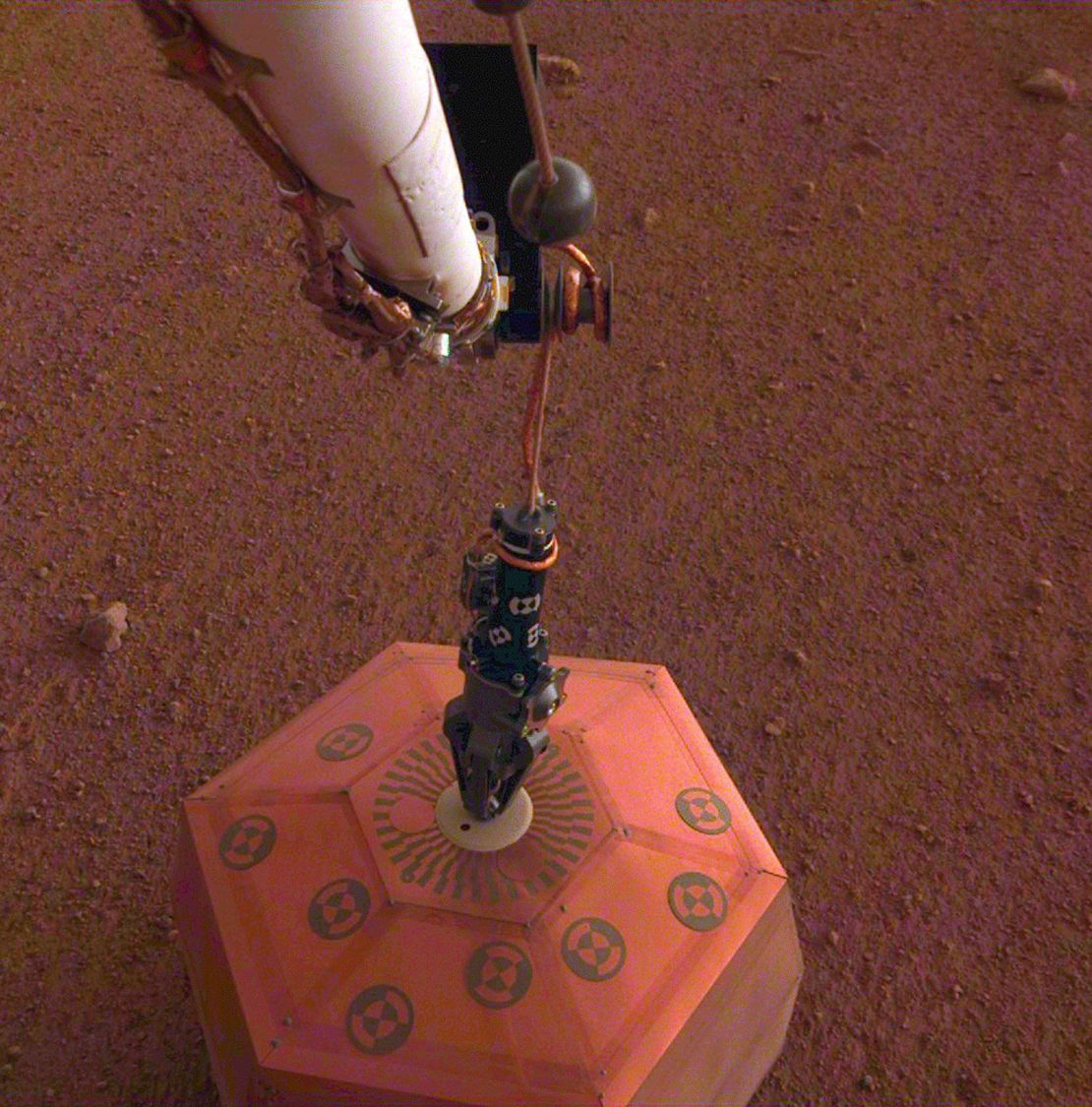

The data came from NASA’s InSight probe, which used a seismometer to study the interior of Mars from 2018 to 2022.

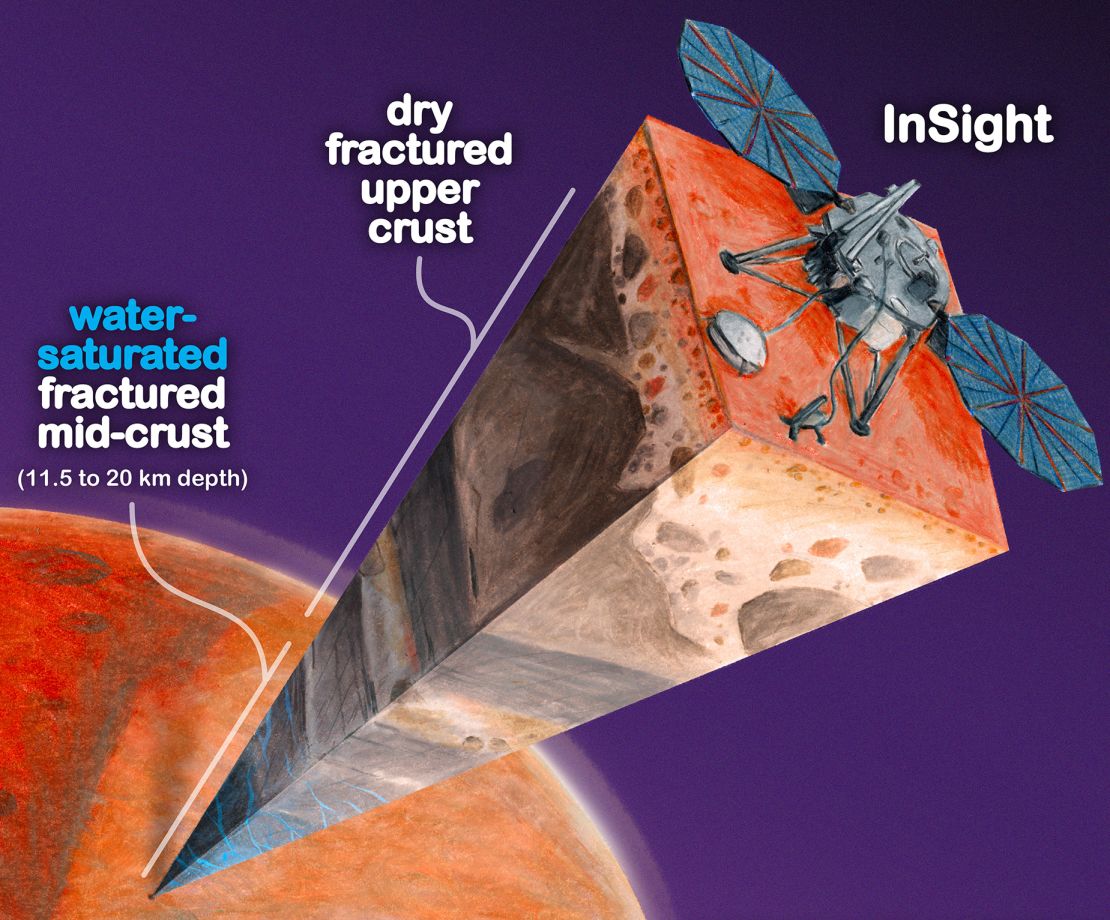

Future astronauts exploring Mars will face a whole host of challenges if they try to access water, because it lies between 7 and 12 miles (11.5 and 20 kilometers) below the surface, according to the study published Monday in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

But the discovery reveals new details about Mars’ geological history, and suggests a new place to look for life on the Red Planet if water can be found there.

“Understanding the water cycle on Mars is critical to understanding the evolution of the climate, surface and interior,” said Fashan Wright, lead author of the study and an assistant professor and geophysicist at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego, in a statement. “A useful starting point is to determine where and how much water is present.”

Mars was likely a warmer, wetter place billions of years ago, based on evidence of ancient lakes, river channels, deltas and water-altered rocks studied by other NASA missions and observed by orbiters. But the Red Planet lost its atmosphere more than 3 billion years ago, effectively ending the wet period on Mars.

Scientists are still not sure why Mars lost its atmosphere, and several missions have been developed to find out the history of the planet’s water, where it went, and whether the water created conditions that would have supported life on Mars. While the water remains trapped in the form of ice in the planet’s polar ice caps, researchers don’t think that can explain all of the planet’s “lost” water.

Existing theories offer a few possible scenarios for what happened to Mars’ water after Mars lost its atmosphere: some hypothesize that it turned to ice or was lost to space, while others suggest that it was incorporated into minerals beneath the planet’s surface or seeped into deep aquifers.

New findings suggest that water on Mars seeped into the Martian crust.

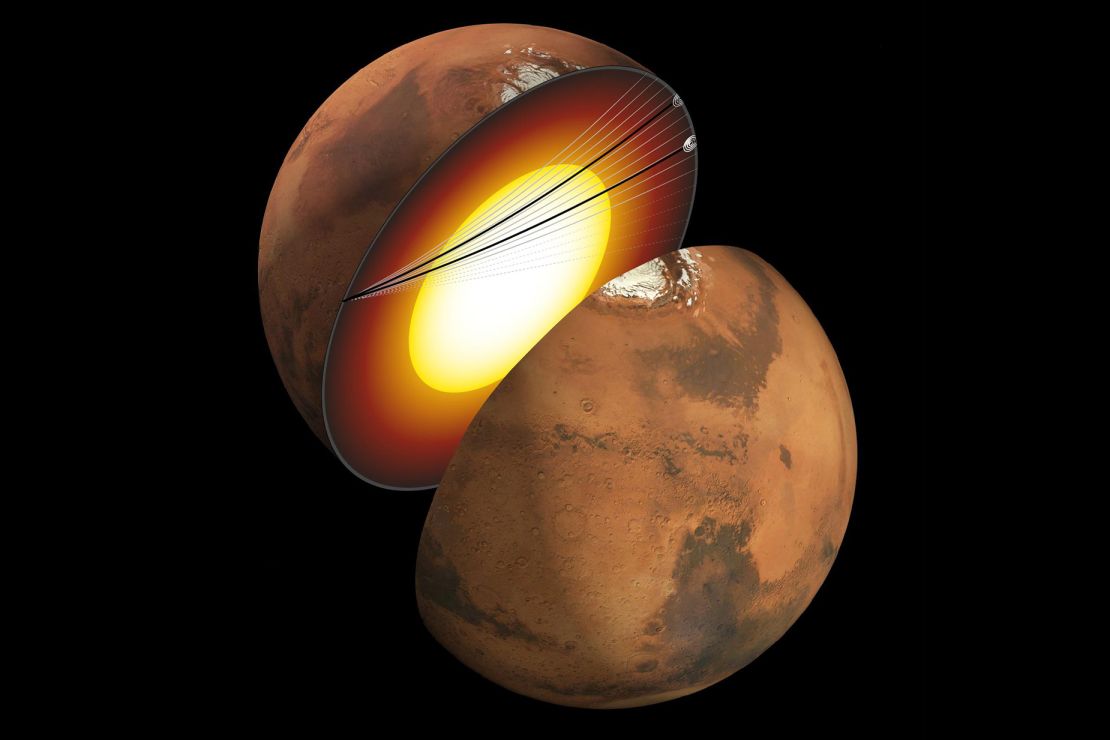

InSight, which stands for Interior Exploration using Seismic Investigations, Geodesy, and Heat Transfer, was a stationary lander. But it gathered unprecedented data on the thickness of the Red Planet’s crust and the temperature of its mantle, as well as the depth and composition of the core and atmosphere. The lander’s seismometer also detected the first quakes on another planet, dubbed “Marsquakes.”

While earthquakes occur when tectonic plates move, shift and collide with each other, the Martian crust is like a giant plate with cracks and fractures as the planet continues to shrink and cool over time. As the Martian crust expands, it cracks, and InSight’s seismometer has detected more than 1,300 Martian earthquakes from hundreds and thousands of miles away.

Scientists studying InSight data were able to study the speed of Martian quakes as they traveled across the planet, which could serve as an indicator of materials beneath Mars’ surface.

Wright said the speed of seismic waves depends on the nature of the rocks, where the cracks are, and what fills those cracks.

The team used this data and fed it into a mathematical model of rock physics, which is used on Earth to map oil fields and groundwater.

The results showed that the InSight data best matched a deep layer of igneous or volcanic rock filled with liquid water.

“The evidence of a large reservoir of liquid water provides some window into what the climate was or could have been like,” Michael Manga, a professor of Earth and planetary sciences at UC Berkeley and co-author of the study, said in a statement.

“Water is essential for life as we know it,” Manga added. “I see no reason why an aquifer would be uninhabitable. That’s certainly true on Earth – deep mines host life, the ocean floor hosts life. We haven’t found any evidence of life on Mars, but we have at least identified a place that could in principle support life.”

If the Martian crust is similar across the planet, there may be more water within the middle crustal region than “the amounts proposed to fill the hypothesized ancient Martian oceans,” the authors wrote in the study.

Rocks help piece together information about the planet’s history, Wright said, and understanding a planet’s water cycle can help researchers understand the evolution of Mars.

Although data analysis cannot reveal any information about life, past or present, if it ever existed on Mars, it is possible that the wet Martian crust could be habitable in the same way that deep groundwater on Earth is habitable for microbial life, he said.

But even drilling holes half a mile (one kilometer) or deeper on Earth is a challenge that requires energy and infrastructure, so it would be necessary to bring a huge amount of resources to Mars to drill to such depths, Wright said.

The team was surprised to find no evidence of a frozen groundwater layer beneath InSight, since that part of the crust is cold. The researchers are still trying to determine why there is no frozen groundwater at lower depths above the middle crust.

These results add a new piece to the puzzle of water on Mars.

The idea that liquid water exists deep beneath the surface of Mars has been around for decades, but this is the first time that real data from a Mars mission has been able to confirm such speculation, said Alberto Ferrin, an interdisciplinary planetary scientist and visiting astrobiologist in Cornell University’s Department of Astronomy. Ferrin was not involved in the study.

He said the water might be “some kind of deep underground mud.”

“These new results demonstrate that liquid water is indeed present in the interior of Mars today, not in the form of discrete, isolated lakes, but as liquid-water-saturated sediments, or aquifers,” said Vereen. “On Earth, the subsurface biosphere is truly vast, containing most of the biodiversity of primitive organisms on our planet. Some investigations even point to the origin of life on Earth deep in the interior. So the astrobiological implications of confirming the existence of liquid water habitats kilometers below the surface of Mars are truly exciting.”

“The result is exactly the kind of thing I was hoping we would get from InSight,” said Bruce Banerdt, InSight’s principal investigator.

“I was hoping we would get good enough data to do this kind of study where we’re actually looking at details inside Mars that are relevant to geological questions, questions about Mars’ habitability, questions about Mars’ evolution,” he said.

Bannert, who was not involved in the research, said that while the interpretation of the data presented in the paper is strongly supported by good arguments, he also believes it is still somewhat speculative and that there is almost always another way to interpret any given set of data.

“I really liked the fact that Wright and others brought mineral physics concepts to the interpretation of seismic data,” Bannert said.

Both Banerdt and Wright have expressed interest in being able to send more seismometers to Mars and other planets and moons in our solar system in the future. While InSight’s single seismometer has collected critical data, deploying it across Mars could reveal variations within the planet and provide a greater window into its diverse and complex history, Banerdt said.

“Just as on Earth, where groundwater connects to the surface through rivers and lakes, this was certainly the case on early Mars as well,” Wright said. “The groundwater we see is a record of that past.”

“Beer aficionado. Gamer. Alcohol fanatic. Evil food trailblazer. Avid bacon maven.”