By any measure, that is Andes Mountains Very, very big. Stretching 8,900 kilometers (5,530 mi) across South America, they arrive It reaches a height of 7 km (4.3 mi) and sIt reaches 700 km (435 mi) in width.

But how did the range grow to such a massive scale? Plate tectonics—the movement of great plates of Earth’s crust across the planet—can create mountain ledges where slower parts are forced up by faster-moving areas.

Although the concept is simple in theory, tracking the speed of tectonic movements over time scales shorter than 10 to 15 million years is challenging for geologists.

Researchers from the University of Copenhagen used a Recently developed method For a more detailed look at the movement of the South American plate that formed the Andes. They identified a 13 percent slowdown in parts of the plate about 10 to 14 million years ago, and a 20 percent slowdown between 5 and 9 million years ago — enough to explain some of the features we see today.

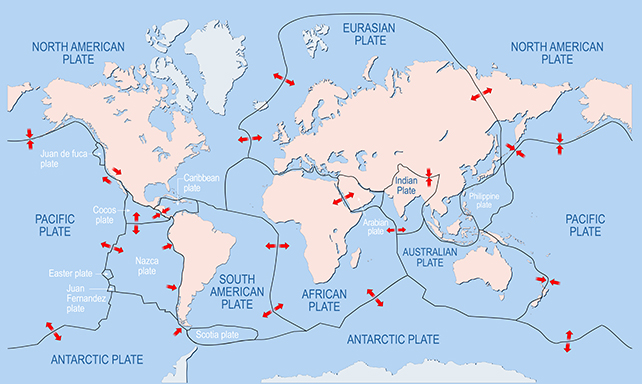

“In the epochs before the two slowdowns, the plate just to the west, the Nazca Plate, pushed into the mountains and compressed them, causing them to lengthen,” He says Geologist Valentina Espinosa of the University of Copenhagen in Denmark.

“This result could indicate that part of the pre-existing range acted as a brake on both the Nazca Plate and the South American Plate. As the plates slowed, mountains grew instead.”

The technique used in the study begins with absolute plate motion (APM), which is the movement of the plates in terms of fixed points on Earth. APM is determined mostly by studying volcanic activity in the crust, as magma tracks tell geologists how the plates have changed.

Then there is relative plate motion (RPM), the movement of the plates relative to each other. This is calculated using a broader range of clues, including magnetization data embedded in the ocean floor that indicates rock movement, and provides a higher resolution (smaller timescale) than the APM data.

To determine the rate of movement in the South American plate, geologists used high-resolution RPM data to estimate APM via some detailed math. By cross-checking the predicted data with geological data we’re sure of, the method allows experts to learn more about the interactions between tectonic plates.

This method can be used for all panels, as long as high-resolution data is available. He says Geologist Giampiero Ivaldano of the University of Copenhagen.

“It is my hope that such methods can be used to improve historical models of plate tectonics and thus improve the opportunity to reconstruct geological phenomena that remain unclear to us.”

The team also considered the question of why these two significant slowdowns occurred in the first place. While a few million years is a long time to us, it is a hypothetical blink of an eye on geological time scales.

One possibility is that convection currents in the mantle have changed, shifting different densities of material around it. It’s also possible that a phenomenon called degassing is responsible, where large portions of the plate sink into the mantle. Both events had indirect effects that affected the movement rate of the plate.

More research and more data will be needed to find out for sure, and the new analysis method will help with that. Even with one (maybe) question answered, there’s a lot to work through.

“If this explanation is the correct one, it tells us a lot about how this massive mountain range came to be,” He says Spinoza.

“But there’s still a lot we don’t know. Why did it get so big? How quickly did it form? How does the mountain range sustain itself? Will it eventually collapse?”

Research published in Earth sciences and planetary messages.

“Beer aficionado. Gamer. Alcohol fanatic. Evil food trailblazer. Avid bacon maven.”