On Wednesday, former NASA administrator Michael Griffin, 73, laid out a respectful but firm stance while addressing a House subcommittee that was holding a hearing on NASA's Artemis program to return humans to the moon.

“I'll be direct,” Griffin said. “In my opinion, the Artemis program is too complex, unrealistically priced, threatens crew safety, poses too great a risk to mission completion, and is unlikely to be completed in time even if successful.”

Essentially, Griffin told the House Subcommittee on Space and Aeronautics, NASA cannot afford to tinker with a complex, partly commercial plan to return humans to the moon, with an eye toward long-term colonization. Instead, he said, the agency should go back to basics and get to the moon as quickly as possible. China, which has a competing lunar program, should not be allowed to outmaneuver NASA and its allies in returning to the moon. He said the space agency needs to “reboot” the moon program and get rid of all this commercial space nonsense.

Griffin's plan

The House members present never pressed Griffin for details about this plan, but it was explained in His written testimony. It's useful reading for anyone who wants to understand where some traditional space advocates would take the American space program if they had their way. It may not be entirely theoretical, as Griffin could seek to return as NASA administrator if Donald Trump is elected president.

In Griffin's case, it would return the country to the comfortable confines of 2008, just before the commercial space age began, and when he was at the height of his power before being fired as NASA administrator. In short, Griffin's plan to accelerate a moon mission requires:

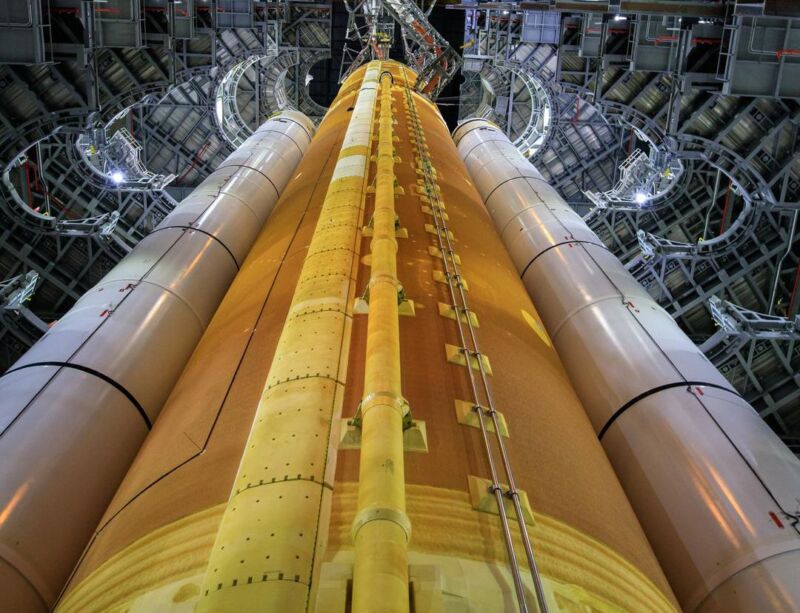

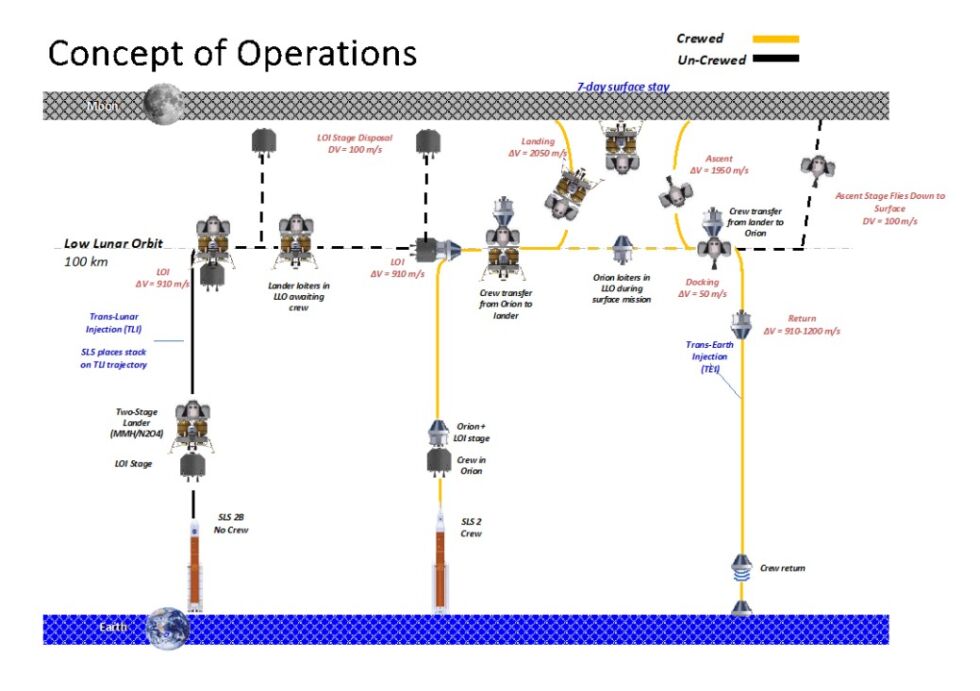

- Two launches of a Space Launch System Block II rocket

- The upper stage of Centaur III

- Orion spacecraft

- A two-stage storable propellant-powered lunar lander

This structure will support a four-person crew on the moon's surface for seven days, Griffin said. “The straightforward approach described here could position U.S.-led expeditions to the Moon beginning in 2029, given bold action by Congress, quick decision-making, and assertive contractor guidance by NASA,” he concluded.

With this plan, Griffin is essentially returning NASA to the constellation program that Griffin helped create in 2005 and 2006. The Orion spacecraft is the same, and the rocket (SLS Block II instead of Ares V) is similar. The proposed lunar lander looks somewhat like the Altair lunar lander. He's trying to put the group back together, relying on Boeing, Lockheed Martin, and Northrop Grumman to get the astronauts back to the moon in a quick and efficient manner.

Testimony of Michael Griffin

The problem with Griffin's plan is that it failed miserably 15 years ago. The independent Augustine Commission, which reviewed NASA's human spaceflight plans in 2009, found that “[t]The United States' human spaceflight program appears to be on an unsustainable path. “It is the perpetuation of the risky practice of pursuing goals that do not match the resources allocated.” Perhaps that is putting it politely.

There are some huge fantasies in Griffin's plan. The first is that there will be two SLS Block II rockets ready for launch in 2029. Remember, it took 12 years and $30 billion to develop the Block I version of the rocket. NASA expects the interim version, Block 1B, to be ready in 2028. But magically, NASA will have two versions of the more advanced Block II rocket (with more powerful side-mounted boosters) ready by 2029.

Then there is the lunar lander. It is not designed. It is not funded. If built through the cost-plus acquisition strategy outlined by Griffin, it would undoubtedly cost $10-$20 billion and take a decade based on past performance. One reasonable estimate for Griffin's plan, based on the contractor's performance with Orion (in development since 2005) and the SLS rocket, is that if NASA's budget roughly doubles, humans could land on the Moon by the late 2030s.

“Beer aficionado. Gamer. Alcohol fanatic. Evil food trailblazer. Avid bacon maven.”