While the few minutes it takes for the spacecraft’s booster rocket to claw its way out of Earth’s gravity may be the mission’s most perilous stretch, there are an incredible number of things that still need to be done before anyone on Earth can truly relax. Space is about as unforgiving as you can imagine, and once your carefully crafted craft is on its way to the black, there’s not much you can do to help it if things don’t go according to plan.

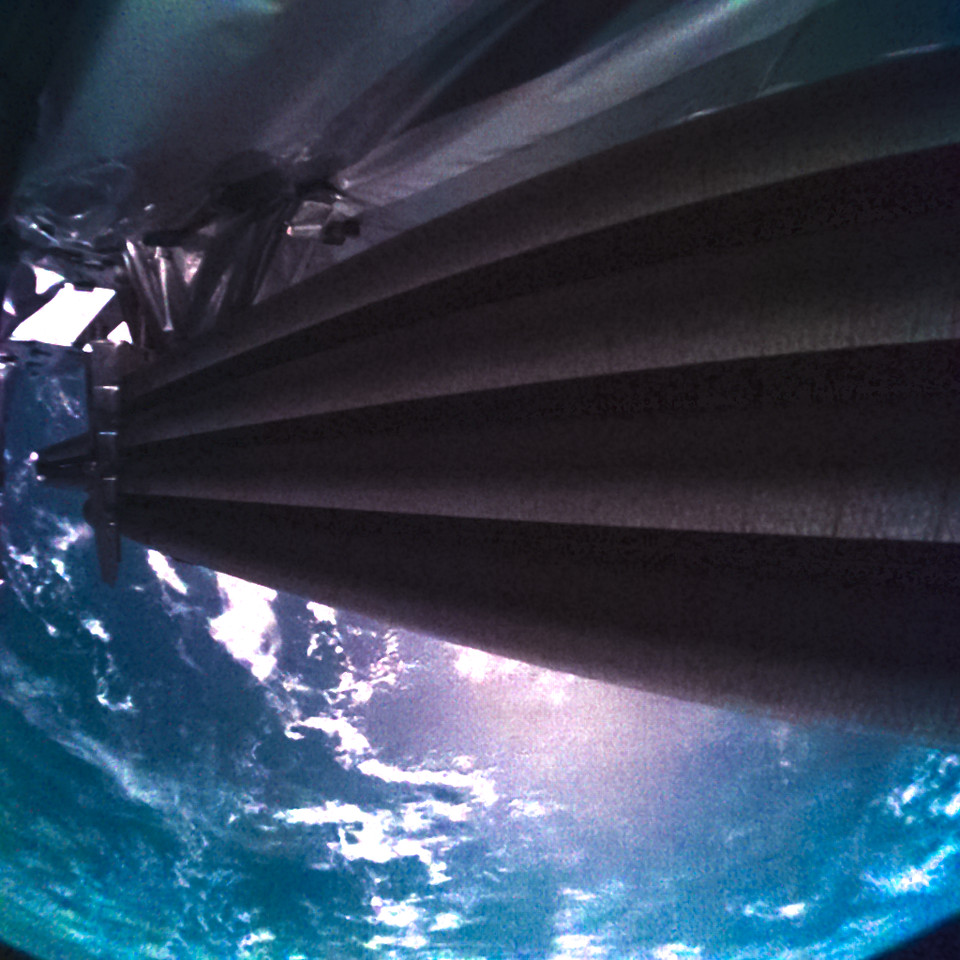

This is exactly where the The European Space Agency (ESA) is currently finding itself With the Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (Juice) spacecraft. The April 14 launch from the Guyana Space Center went off without a hitch, but when the probe’s 16-meter (52-foot) radar antenna was ordered to untie, something jammed. Judging by the pictures taken from the on-board cameras, the antenna has only been extended to approximately 1/3 of its total length.

The current theory is that one of the launch pins got stuck somewhere, preventing the antenna from moving any further. If so, that could mean shaking the pin a few millimeters will get them back in the game. Unfortunately, there are no gremlins with small hammers stowed in the rover, so engineers on Earth will have to get a little more creative.

It is hoped that the engine burns can be used to rock the craft, possibly ejecting the pin. They’re also looking into rotating the car to move the antenna mount in and out of sunlight — the idea is that some expansion and contraction of the metal components could free things up, too.

Even in the worst case of all, the Radar Antenna for Icy Moons Exploration (RIME) is just one of ten instruments Juice will use to study Ganymede, Callisto, and Europa. So while it would be disappointing if they couldn’t get it online, the mission would still provide a wealth of information about these wonderful worlds.

Then again, Juice isn’t scheduled to reach Jupiter until at least July 2031, so there’s still plenty of time to try and figure something out. After all, it wouldn’t be the first deep space probe saved by a clever hack.

“Beer aficionado. Gamer. Alcohol fanatic. Evil food trailblazer. Avid bacon maven.”