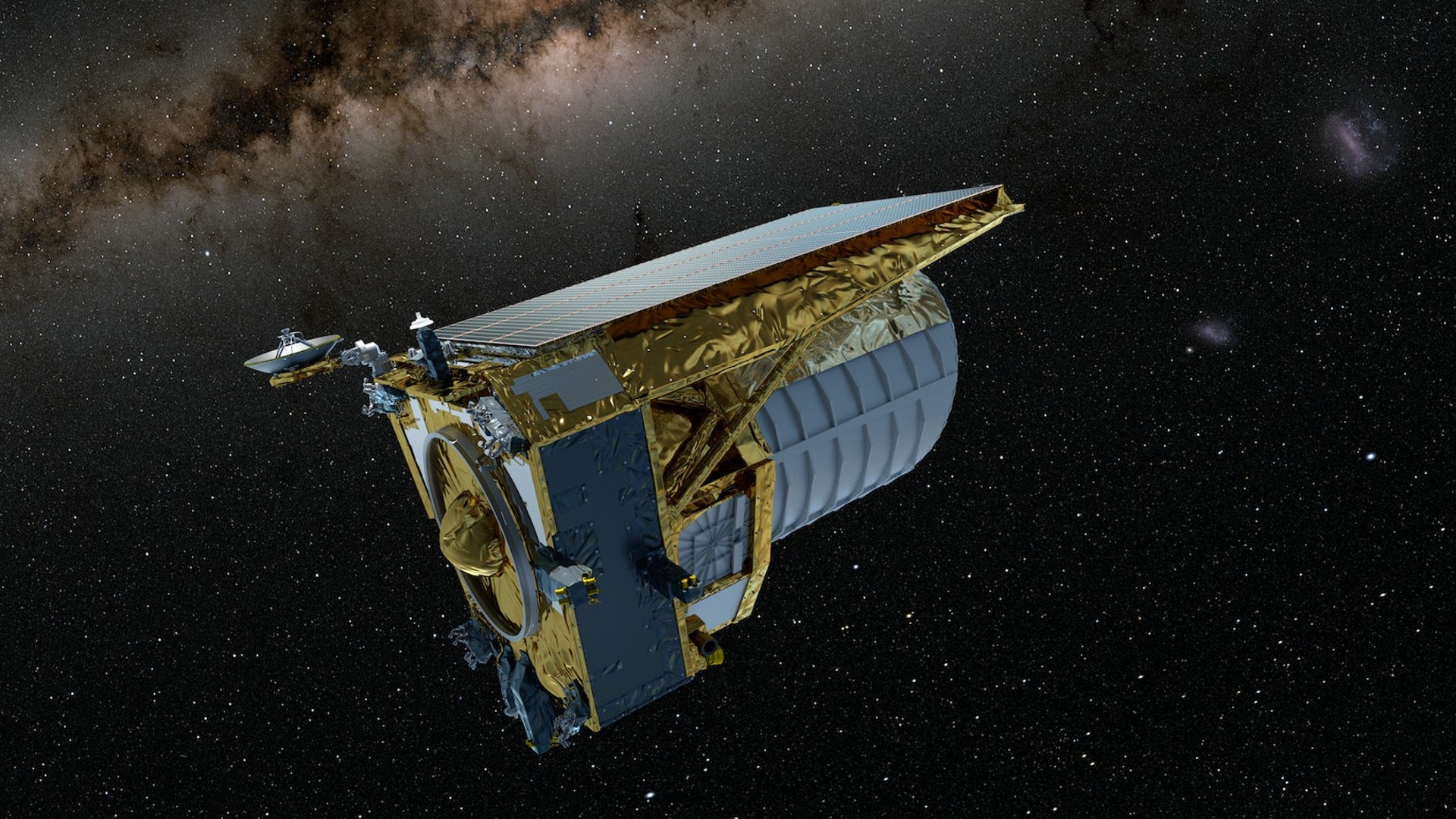

Cape Canaveral, Fla. — A new space observatory is flying through the void after a dramatic launch on the roof of a SpaceX rocket Saturday (July 1), but its journey is just beginning.

The European spacecraft Euclid began its long journey into deep space aboard a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket at 11:11 a.m. EDT (1511 GMT) from Cape Canaveral Space Force Station on the Florida Space Coast.

“You can imagine all the tensions and all the pressures that people are under,” ESA Director General Josef Ashbacher said at a post-launch briefing on Saturday (July 1). He added that not all tension had subsided yet.

Related: How will the European space telescope Euclid see the dark universe?

“It was a really cool launch – from inserting the spacecraft to separating into orbit,” he noted. But he said the researchers are so worried “that the different tools are running. This takes two weeks.”

The space observatory will now spend the next month moving to the Sun-Earth’s Lagrange Point 2, which is about 1 million miles (1.5 million kilometers) from our planet on the far side of the sun.

Next comes a complex series of tests and observations to make sure its instrument is ready to go before it can be scanned for its ultimate mission: finding evidence of invisible dark matter and dark energy and how it shaped our world, Euclid Project Director Giuseppe Racha told Space.com.

Related: We’ve never seen dark matter or dark energy. How do we know it exists?

Now that Euclid is in space and sending signals home, his first task is to get himself on track for L2. It will happen about two days after launch, and its trajectory will be checked along the way to make sure it’s heading in the right direction.

The first month of Euclid’s spaceflight will see it fly into L2, which naturally cools down to the temperatures of space, while all instruments and systems will be scanned for space. Then, months two and three will see engineers evaluate Euclid’s performance against what we’d expect on the ground (which will, perhaps, include releasing some calibration images—though mission representatives are tight-lipped about timing).

“After that total of three months, we should be ready to start science observations, but we still have to do some special calibration until then,” Racha said. Euclid will probably be fully ready in about eight months, assuming nothing goes awry during testing.

The long calibration sequence is similar to what NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope experienced after its launch and journey to L2, which thankfully happened with minor calibration issues. JWST stares at very small parts of the universe in high detail, while Euclid will instead scan large areas of the sky for the bending of light around stars or galaxies. This is a telltale sign of the dark universe.

Racha said team members will be particularly concerned about image quality, which can be affected by things like humidity — an irony considering Euclid was launched from Florida during a typical wet July day. “Just a few nanometers of water ice in our optics affects our image quality,” he said.

Fortunately, there’s a back-up plan if Euclid gets a little stray moisture, but mission project scientist Rene Lorigs told Space-Profound.org it would be tough.

“If we have pollution, we have to heat the satellite to cool it down again to get rid of the moisture,” he said. “In principle, we could do it. But it will make a hole in our schedule.”

Euclid needs to move quickly to map out 15,000 square degrees (one-third of the sky), so he’ll watch the team anxiously to make sure he’s ready to go. If there is a need for dehumidification, Lorigs said, it will be difficult to “finish the wipe on time,” but there is still room for that.

Elizabeth Howell’s trip to Florida was jointly sponsored by Canadian Geographic and Canada’s University of Waterloo, where Euclid’s primary science coordinator (Will Percival) is based. Space.com has independent control of news coverage.

“Beer aficionado. Gamer. Alcohol fanatic. Evil food trailblazer. Avid bacon maven.”